Whispers in the Wings: Friends Break Silence on Emily Finn’s Final Days

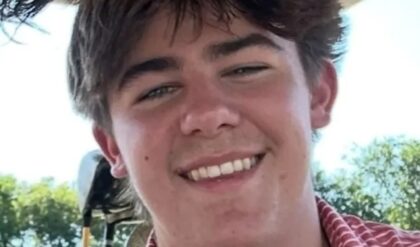

In the quiet coastal enclave of Sayville, Long Island, where autumn leaves swirl like forgotten pirouettes, the community grapples with a loss that defies the grace of its most cherished daughter. Emily Rose Finn, an 18-year-old ballerina whose lithe form once commanded the stage at the American Ballet Studio, was fatally shot on November 26, 2025, in a Nesconset home that should have marked a simple closure to a chapter of young love. Police describe it as a botched murder-suicide: Emily, home from SUNY Oneonta for Thanksgiving break, arrived at her ex-boyfriend Austin Lynch’s residence around 11 a.m. to return his belongings. Minutes later, two shotgun blasts shattered the morning— one ending her life, the other grazing Lynch’s face in a self-inflicted wound that left him hospitalized but alive. Now 18, Lynch faces second-degree murder charges, his bond set at $1 million as Suffolk County prosecutors prepare a case laced with digital breadcrumbs of obsession.

What began as a seemingly amicable split has metastasized into a narrative of quiet dread, amplified this week by the first public voices from Emily’s inner circle. In a candlelit vigil at her former dance studio on December 2, friends—some still wiping away tears from her December 1 funeral—spoke haltingly of a breakup that was “far from dramatic,” yet shadowed by an unease that now feels prophetic. “It was just… silence,” said Maia Toth, Emily’s high school confidante and fellow SUNY freshman, her voice cracking under strings of pink ribbons tied in Emily’s honor. “Late texts, like hours to respond. She’d say, ‘He’s not mad, just… processing.’ But we saw it in her eyes—the way she’d check her phone like it was a bomb.”

The couple’s romance, chronicled in prom photos unearthed by the New York Post, painted a picture of teenage idyll: Emily in a flowing magenta gown, Lynch in crisp black, twirling on a candlelit dance floor just months earlier. They met as juniors at Sayville High School, bonding over shared dreams—hers of teaching dance to inner-city kids, his of enlisting in the Marines. Social media brimmed with snapshots: beach sunsets, coffee dates, her tagging him in posts about “my favorite partner in crime.” But as graduation loomed in June 2025, fault lines emerged. Emily headed to SUNY Oneonta for a degree in childhood education with a dance minor, while Lynch deferred college for boot camp. “Distance was the killer,” Toth explained during the vigil, where over 200 gathered, many in pink—Emily’s favorite hue—to light lanterns shaped like tutus. “She wanted to grow, travel, live that college chaos. He… couldn’t let go.”

The breakup unfolded in whispers over late-summer texts, not fireworks. Emily confided in a group chat with three close friends that Lynch had grown “distant but clingy”—periods of radio silence followed by floods of messages demanding updates on her dorm life. “It wasn’t yelling or anything explosive,” recalled sophomore classmate Lila Chen, who roomed with Emily briefly at SUNY. “Just this slow pull-away. She’d laugh it off, say he was ‘losing his cool’ over nothing, like her posting a story with guy friends from class.” But beneath the levity lurked a fear that friends now describe as visceral: Emily’s dread of Lynch “losing control.” Chen shared a screenshot from their chat, timestamped September 15: “IDK, he texts like he owns my schedule. What if he snaps? Feels like I’m walking on glass.”

That sentiment crystallized in the hours before the tragedy. On November 25, the eve of Thanksgiving break, Emily met a classmate for coffee in Oneonta’s bustling quad. Over pumpkin spice lattes, she voiced a chilling unease: “I feel like I’m being watched.” The friend, who asked for anonymity out of respect for the family’s privacy, told CBS New York that Emily scanned the parking lot twice, attributing it to “paranoia from finals stress.” But hindsight sharpens the horror—Lynch’s phone records, subpoenaed by investigators, show pings near Emily’s campus that week, unexplained drives from Long Island. “She brushed it off as silly,” the classmate said, clutching a pink ribbon at the vigil. “But now… God, if we’d pushed her to block him sooner.”

The final voicemail, recovered from Emily’s iPhone on November 28, adds a layer of gut-wrenching finality. Timestamped 10:47 a.m. on the 26th—moments before she drove to Nesconset—it captures her voice, steady but laced with resolve: “Hey, Austin. I’m coming over to drop your stuff. Let’s keep this clean, okay? No drama. I care about you, but this is it. Block me if you have to, but don’t make it weird.” The 45-second clip, never sent, sat in her drafts folder, a digital ghost discovered by her mother, Karen Miller-Finn, during a tearful sift through Emily’s belongings. Miller-Finn revealed its existence at the funeral, her eulogy a raw tapestry of grief and fury. “My pure angel,” she said, voice breaking as pink-clad mourners—family, her brother Ethan, grandparents—clutched tissues. “She told me that morning, ‘Mom, I’m scared he’ll lose it.’ Prophetic words from a girl who saw the storm coming but walked into it anyway.”

Emily’s light, as her former instructor Kathy Kairns-Scholz eulogized, was “a beautiful performer who knew everything—choreography, kindness, the steps to lift others up.” At the American Ballet Studio in Bayport, where Emily danced since age 5, pink ribbons festoon the doors, and this year’s “Nutcracker” production—set for December 14—will dedicate its Sugar Plum Fairy solo to her memory. A scholarship in her name, announced December 3, aims to fund dance for underprivileged girls, echoing her dream of teaching beyond the barre. “She had everything ahead,” Kairns-Scholz told Newsday, eyes misty. “Picked up routines like breathing. There wasn’t a soul she didn’t touch.”

The community’s response has been a swell of pink solidarity: Trees wrapped in ribbons along Sayville’s Main Street, a GoFundMe surpassing $85,000 for funeral costs and advocacy, and the Youth Peace and Justice Foundation pledging an annual Emily Finn Scholarship. Cousin Francis Finn, speaking to mourners, choked out, “She had the world ahead, loved and missed beyond words.” Yet amid the tributes, anger simmers. X (formerly Twitter) erupts with #JusticeForEmily, posts decrying “puppy love turned predator” and calls for stricter gun laws—Lynch’s shotgun was legally owned by his father. One viral thread from @SeeRacists, viewed over 500,000 times, frames it as “America’s problem: obsession unchecked.” Advocates like Break The Silence Against Domestic Violence highlight the “escalating obsession,” urging hotlines: 1-855-BTS-1777.

For Miller-Finn, the voicemail is both torment and talisman. “She was brave, my girl,” she told the Post, clutching the phone like a relic. “Told me she felt watched, like shadows followed her home. Friends say the breakup was quiet, but he stewed. Late replies turned to demands. That fear of him ‘losing control’—it wasn’t hyperbole.” Suffolk County DA Ray Tierney, in a December 4 briefing, vowed a swift trial: “No prior domestic calls, but texts paint obsession. Emily deserved better.”

As winter bites, Sayville’s ballet studio dims its lights for a moment of silence each evening, whispers of pliés echoing Emily’s unfulfilled spins. Friends like Toth and Chen, who tied the first pink ribbon, vow to carry her grace forward—organizing self-defense workshops, amplifying stories of “watched” women. “She confessed that fear hours before,” Toth said, lantern flickering. “We speak now so others don’t whisper alone.”

Emily Finn’s story, once a pas de deux of promise, ends in a solo of sorrow. But in the silence after the curtain falls, her voice—unsent, unbroken—urges vigilance. In a world where love can curdle to control, her final words demand we listen closer, act swifter, and wrap the vulnerable in more than ribbons.