Today’s guest post is by Gregory Maguire, author of over 40 books for adults and children, most famously Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West, a 1993 best-seller which went on to become the basis of the musical Wicked, one of the longest running shows in Broadway history. The play was recently transformed into a blockbuster film, starring Cynthia Erivo and Ariana Grande, playing at theaters everywhere.

A gay Catholic, who, with his husband, Andrew Newman, raised three adopted children to adulthood, Gregory led a workshop during New Ways Ministry’s Sixth National Symposium in 2007 about families headed by gay and lesbian people. He also spoke about his family’s life at a press event entitled “Five Minutes with the Pope,” during Pope Benedict XVI’s visit to the United States in 2008.

I came to write the novel I called Wicked: The Life and Times of the Wicked Witch of the West in 1993. I’d been thinking about it for a number of years, but was waiting until I felt my confidence in my skill set could see me through the task. I began the novel in London, on the day I turned 39.

My birth mother had died in hospital a week after I was born, from complications due to bringing me into the world. While I had a wholly supportive second mother—my birth mother’s best friend from childhood, as it happens—the heavy weight of the narrative tale of my birth weighed on me up until then. Frankly, it weighs on me still. I didn’t ask to be born, and my first mother didn’t ask to die. But the tragedy happened, and I had to live with a certain inevitable sense of culpability.

I was born into a Catholic household, in a Catholic neighborhood—most neighborhoods in mid-century Albany, New York, were Catholic, it seemed. So I slogged through childhood, panting: breathing in the concepts of obligation, of moral debt, of responsibilities to shoulder with every intake; and breathing out the fear that I would not be up to the task that it seemed God had set me. What task? Of living a life of enough virtue, and of benefit to others, that I could somehow rectify the cost of my existence. I felt, and by the time I was about twelve I could state, that my life had to be twice as fruitful, in order to compensate the spirit and soul of my dead mother, whom I believed was watching over me and my three older siblings.

But when I was about sixteen and the first twinges of attraction to other boys began to make themselves known, I fell into a torment of guilt. Was it for this that my mother had died, that I should grow up queer—twisted—defective? What a cruel joke. The three i’s, I considered it then: Illegal. Immoral. Ill.

I suppressed the rising sense of horror as long as I could. I was in denial, I suppose; I couldn’t be sure. And in my generation, at least in my provincial Irish-Catholic setting, the concept of “experimentation” was hardly discussed, let alone entered into. I mean, if sexual practice among heterosexuals wasn’t mentioned by parents to teenagers, then, the possibility or even existence of homosexuality wasn’t even whispered in locker rooms. I think many younger people growing up now in an era of accessibility and of identity politics can’t imagine how abandoned, shipwrecked, a gay boy in a Catholic high school could feel. As alone as a green-skinned Elphaba, isolated with no peers in a world of safely ordinary citizens.

While I could read well enough, and understood the story of Oscar Wilde and what some (few) boys were doing when they taunted the more sensitive or queer-reading boys among us (I was rarely the target, mercifully for me), the reality of what it all actually meant—when it came to love, when it came to passion, or to promise—seemed like a great black chalkboard slate on which no one, ever, had written a legible word. I knew about Michelangelo and maybe Shakespeare and Oscar Wilde. But I didn’t meet anyone personally who was gay and out until after I’d graduated from college–though I did encounter people who acted on affection and even romance, including a few men who loved me, somehow.

What helped me survive this bizarre blizzard of ignorance was the very thing that threatened me the most: my Catholic faith and identity.

I’m not going to try to defend or even define what my faith means to me now. I have long ago concluded it is a task beyond my power of articulation. Anyway my understanding of just how pious or how skeptical I am whips about with all the geo-locatability of an untrackable electron, according to what the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle claims. But what I can claim is that Being Good seemed at least twice as necessary for me as church teaching required, as Jesus required, since I had to be good on behalf of myself and of my dead mother, too.

Original book cover design from the 1990s

I considered suicide, though not very fervently. The church taught that suicide was a mortal sin. Not to be reunited eventually with my mother in heaven made such a solution impossible. I also read Daniel C. Maguire’s (no relation), Death by Choice. A respected theologian, he didn’t provide me a way to make such a choice. On the plus side, I grew up in an era when Catholic guidance counselor’s offices had uplifting posters stating that “God don’t make no junk,” a Black pride slogan that was usefully co-opted for just about any Catholic high school moral crisis. I believed in the goodness of God and the mystery of God’s plan, and the sacred grace of discernment. I figured I had no options but to tough it out, figure it out, and learn what God had in store for me, something that no beloved nun or priest could name, and no parent would dare to raise in conversation.

So I sublimated my pain and my sense of isolation. Of course I did. Most of us do. But because I grew up in a household that relished writing and reading, and funny storytelling at dinner, a household whose only real perq was an abundance of library cards among nine of us, I read in order to survive. Yes; it wasn’t the good nuns and worthy priests, the hard-working and emotionally timid parents who rescued me. It was the library.

I read about Aslan and the suffering creatures of Narnia, turned frozen in the endless winter of the White Witch. I saw Aslan’s forgiveness toward the sinner, Edmond, I wept over how Meg Murray, in A Wrinkle in Time,was able to save her baby brother through the power of love (with lots of Christian symbolism to remind her what she was up to).

And I took my cues about how journal-keeping could build the heart and mind of a writer from Louise Fitzhugh’s Harriet the Spy. I bought a spy notebook, began to observe the world, and thus (eventually) to understand and unpack myself. I taught myself to be honest, and to honor honesty, even if it felt cruel to speak some thoughts aloud (to the secret page).

And so my being a Roman Catholic and my being gay, a seemingly intractable pair of characteristics, were joined by a third identity: that of being a writer.

Which brings us, through Narnia and through love, to my living in England when I turned 39, and beginning to feel my time had come. If I was one day older than my mother had ever been—she died at the age of 38—then I was, by definition, a grown-up. (No one ever counts on being older than their mother.) Starting out as a children’s writer, I felt I had to be old enough to write a grownup novel now. I put aside my fears and hesitations, I bought a new notebook, and I began to write Wicked by hand. It was published when I was 41, nearly thirty years ago.

Is Wicked about being gay, is it about being Christian in any way? Not explicitly. But I did try to put in the fabric of my anthropological look at L. Frank Baum’s original merry-land of pasteboard, nonsense, and vaudeville something of the moral seriousness of Middle-earth and of Narnia. For one thing, I claimed faith for Oz—faith abroad in Oz. Not magical faith, as in Narnia, not a faith of miracles and interventions, but human faith, practiced and often abused. And more than one faith, because my Oz was intended to emulate our own real world with its crusades and creeds, its frictions and its paradoxes.

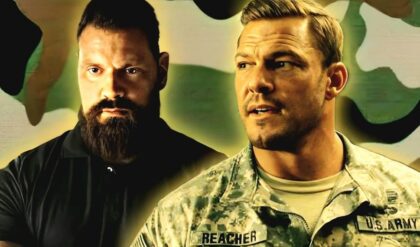

Still photo from the movie “Wicked”: Cynthia Erivo as Elphaba and Ariana Grande as Galinda

I also claimed vaster romantic possibilities for the people of Oz, though I largely indicated this by indirection. Elphaba’s son, Liir, does have a male romance (in the sequel Son of a Witch), and when we meet him again in the middle of The Witch of Maracoor,, five books later in my series, he and Trism are middle-aged, and householders. When people ask me if Elphaba is based on myself, I say every strength of Elphaba’s is my ambition, and nearly every weakness is a self-portrait. But Liir—who is inept, confused, whiney, romantic, a foot-soldier on the road to his own Calvary, probably—Liir is definitely me.

Like Tolkien, whose Christianity came into Middle-earth at a slant, I tried to indicate the strength, the value, the danger of religious fervor in Oz without coming down on the side of one belief system or the other. I tried to be honest. One of Elphaba’s chief motivations in the second half of the novel is the seeking of forgiveness, a project complicated by the fact that she isn’t certain she has a soul. Also, I gave the citizens of Oz more variety of affectional preference, too, and I tried to avoid pathologizing my beloved characters, avoid assigning obvious or direct causes for why people are the way they are.

If you ask, “Is there such a romantic item as Gelphie—a Galinda and Elphaba crush?”—I find I can’t answer that. If you can, answer it to the best of your satisfaction. Your guess is as good as mine.

Most things are unknowable, like the electron path around an atom’s nucleus. For the sake of conversation, and to give ourselves a false sense of stability in a universe whose planets rock as wildly as electrons, we make blanket statements of assurance about this or that. It gives us a tentative and temporary handhold. We’re likely to change our minds sooner or later. In the end, the real challenge is to accept the mystery of unknowing, and to refuse our instinct to compartmentalize, to divide the world between us and them, good and bad, me and you. (Straight and gay, even. Pious and lapsed.) If I can’t even know myself very well, how possibly can I claim to know you? If I can’t be sure if I am a person of faith or a person of wavering faith, or no faith, how can I be sure who you are, and what you believe, or want, or are capable of?

What Wicked strives to do is to beg for patience with ambiguity. In the words of the title of philosopher Alan Watts’ book, The Wisdom of Insecurity–—another literary work that served to keep me functional when I was starting college. I could do this. I could balance on the air. I could make something of myself, and pay off my moral debt. I could, perhaps, defy just a little gravity. For a while. And in writing Wicked, and my other forty-odd books, I could try to comfort others who reach for the handrail they’ve been raised to rely upon, and find it missing.

We become one another’s handrails.

In the opening paragraphs of Wicked , which I recently had reason to revisit, I see that when I describe the Witch flying, Elphaba doesn’t straddle her broom the way a polo player would a horse, or sit side-saddle like a gentlewoman on a fox hunt. No. She uses the broom as a balustrade. This manner of flying is replicated both in the stage play and in the film, mimicking my description in the novel. Elphaba in mid-flight uses the broom as a bannister. For a moment, she has invented her own handrail.

And soon enough it will be time for her to serve as someone else’s handrail. As, I believe, we all yearn to do.

–Gregory Maguire, December 17, 2024