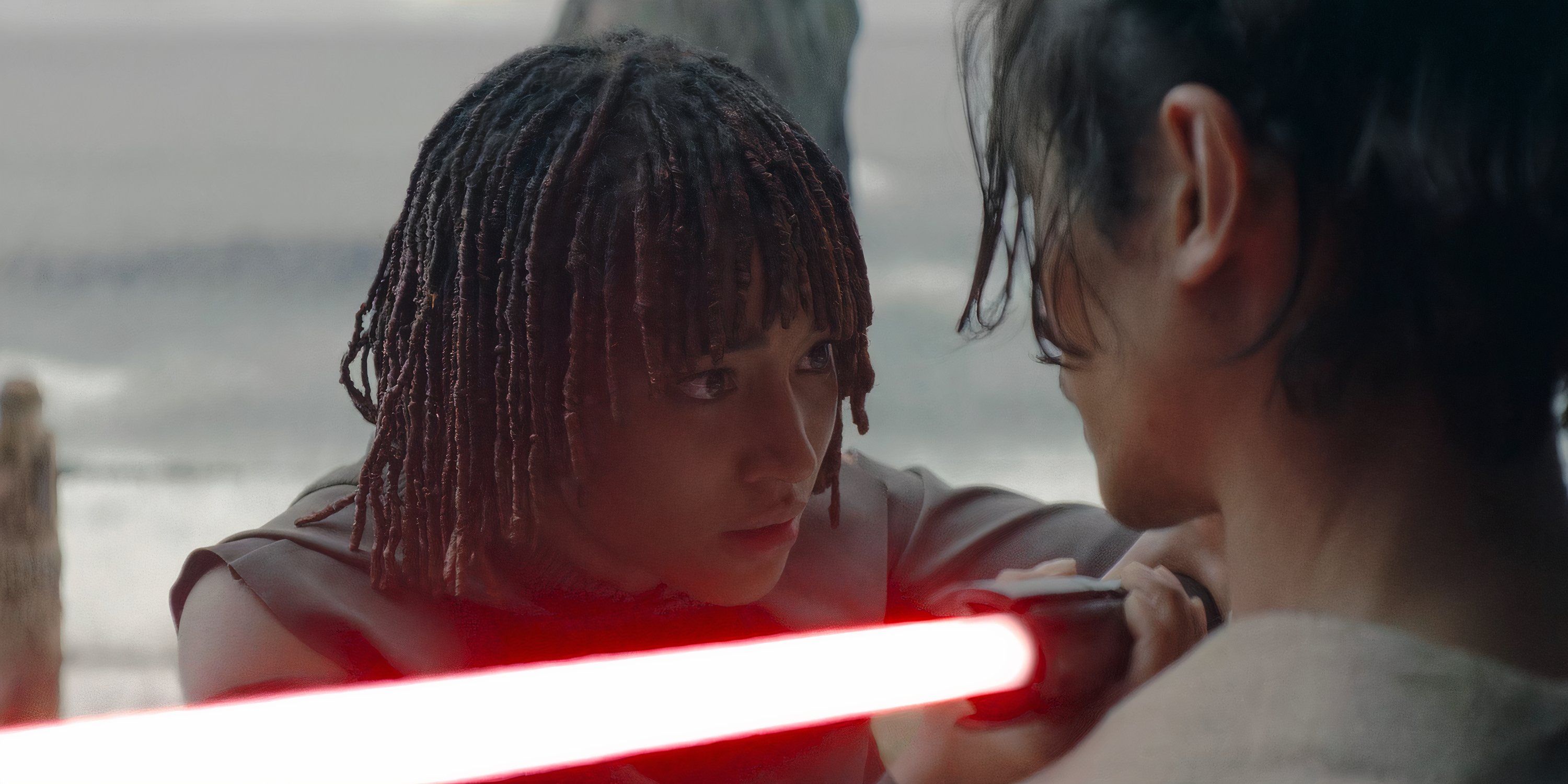

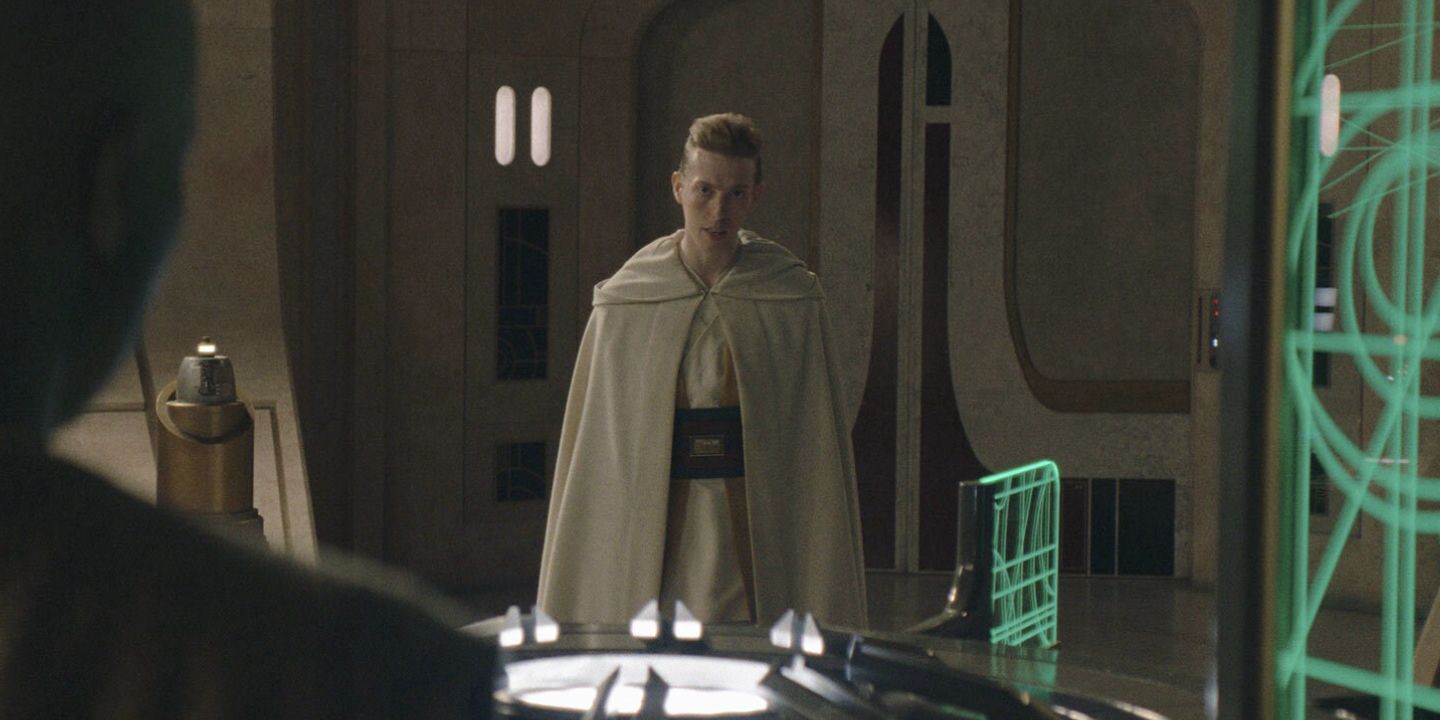

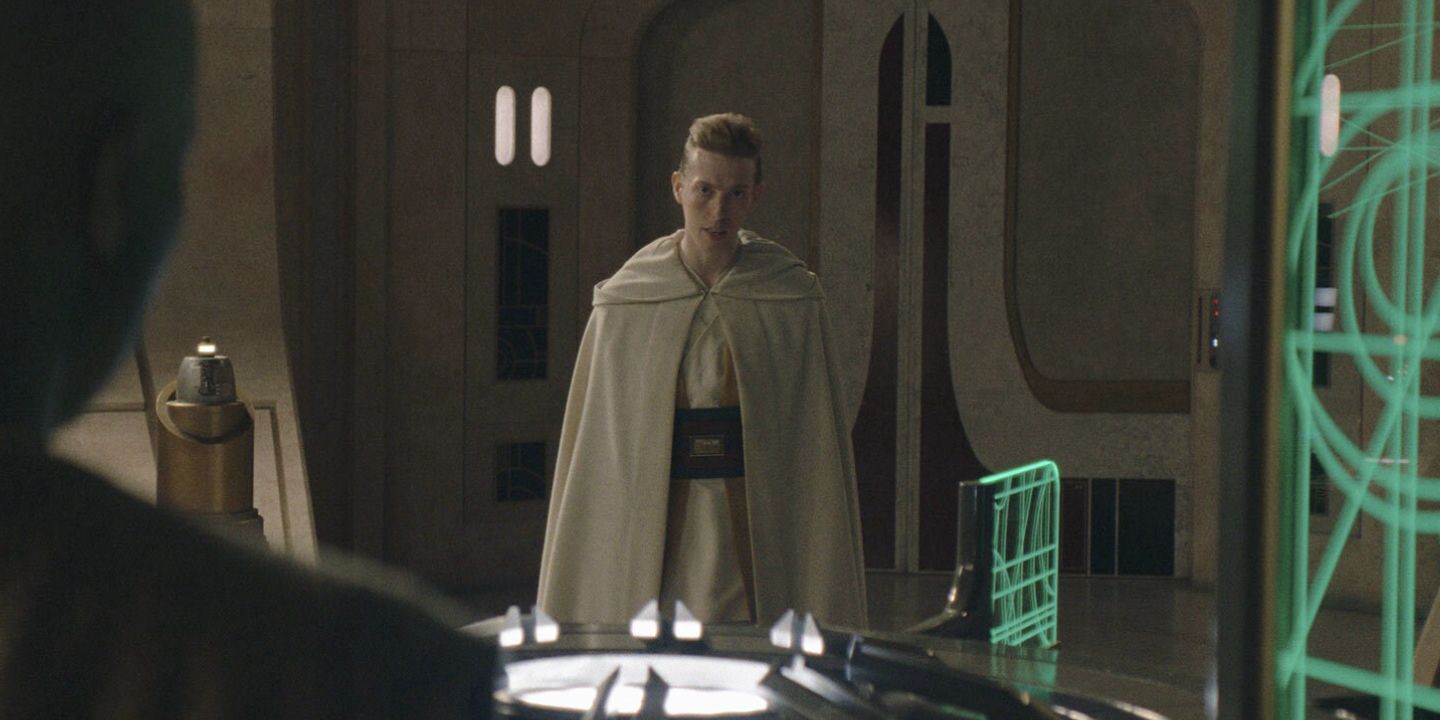

The Acolyte is one of the darker Star Wars shows developed in recent years and chooses to focus on less savory acts and more nuanced themes. While certainly not portrayed as outright evil, the Jedi are presented in shades of gray and the audience is invited to consider different perspectives regarding their actions. Indeed, the core event that sets the stage for the plot, the death of the coven on Brendok, is shown from multiple viewpoints over the course of the series to emphasize the importance of how one perceives reality. While plenty of fans have loved this approach, others are vocally upset about casting the Jedi as a group capable of making rash decisions, covering up their mistakes, and keeping secrets from the leaders of the Republic. This take on the Jedi may be shocking to some but, for those that have been paying attention to Star Wars since the prequels, it shouldn’t be surprising at all.

The Jedi Originally Reflected Arthurian Knights

Lucas drew inspiration from the films of Akira Kurosawa as well as King Arthur and other sources.

Far from heroic figures, knights were soldiers who traded services for privileges from the nobility.

Obi-Wan was first played by Alec Guinness, who was actually knighted in real life.

It’s certainly true that the Jedi, as first depicted in the original Star Wars trilogy, were unambiguously good and noble heroes. Obi-Wan describes them as the “guardians of peace and justice in the Old Republic” early in A New Hope, and he serves the role of a caring mentor and courageous protector throughout the film. Yoda continues this trend in The Empire Strikes Back, showing fans a Jedi master who emphasizes peace and humility in his teachings to Luke. The final film of the trilogy even adopted the title of Return of the Jedi, plainly expressing the idea that the Jedi are a force for good and that their return will mark a new, better era for the galaxy. This take on the Jedi is unsurprising, given George Lucas’ sources of inspiration and the tone of the films.

While set in space, Star Wars borrows a great deal from the fantasy genre, presenting a world with good and evil wizards, princesses to be rescued, and even knights with swords. For these Jedi knights, Lucas plainly drew on the warriors of Arthurian legend.

King Arthur’s Knights of the Round Table inspired the archetype of the pure and just knight that goes on quests and adventures to defeat villains and save the innocent. This is the nature of the Jedi as presented in the original trilogy. Fans see no hints of organization or broader hierarchy and little connection between the Jedi and the politics of the Old Republic. Like Arthur’s knights, they appear to regularly act as lone warriors going off on adventures and, as Obi-Wan says, “crusades,” for the cause of justice. For better or worse, this changed with the prequels.

The Prequels Raised Questions about the Jedi’s Honor

The prequels focused much more on politics, setting up the Galactic Senate and how it worked.

They also filled in the details of the Jedi Order, assigning different ranks and positions.

Fans continue to debate the proper order in which to watch all the movies since the prequels.

For Star Wars’ prequel trilogy, Lucas sought to move away from the simplicity of high fantasy and presented a more complex world. Ultimately, the prequels tell the story of how a once benevolent and successful republic collapsed under the weight of bureaucracy, corruption, and the machinations of a clever, charismatic, and evil political figure. As such, these films show fans a republic in decline and ripe for subversion.In the process, the Jedi get similar treatment.

The Jedi of the prequels don’t come across as quite as corrupt as the republic they serve, but they do have their own problems. At the least, they appear complacent and overconfident, unwilling to accept the possibility of the return of the Sith until it’s too late. They ultimately allow Obi-Wan to train Anakin Skywalker despite their concerns about him, and fail to rein in his darker tendencies.

On top of this, individual Jedi make questionable decisions throughout the films. Yoda chooses to accept the support of a clone army despite obvious ethical issues with using people that have been bred to fight. Qui-Gon shows a willingness to deceive and use the Force to get his way throughout The Phantom Menace. Mace Windu moves to arrest the chancellor of the Republic without informing any political officials, solely on the basis of Anakin’s accusation. While the accusations were true in this case and Palpatine was a threat, this demonstrated a tendency of the Jedi to directly interfere in the democratic process of the Republic without any oversight.

In the end, the Jedi of the prequels plainly had noble intentions, but they were far from the pure and incorruptible knights of the original trilogy. This shift would be expanded on in the Expanded Universe of games, comics, and shows. It would be explored in even greater detail in the sequel trilogy.

The Sequel Trilogy Critiqued the Jedi Further

The sequel trilogy received criticism for its jarring shifts from movie to movie.

The second was written and directed by Rian Johnson, while the others were headed by J.J. Abrams.

The main villain, Rey’s background, and other details, seemed to change from one film to the next.

The Force Awakens appeared to be returning Star Wars to its roots, earning the label of soft reboot from some viewers. It followed a narrative and tone that mirrored A New Hope and seemed to be making the Jedi noble heroes and saviors again. The Last Jedi reversed this.

In Rian Johnson’s entry into the sequel trilogy, Luke made a return that dismayed Rey along with many fans. The young, idealist farm boy who restored the Jedi Order was now a bitter and cynical old man, convinced that the Jedi needed to disappear from the galaxy. Of course, Luke seemed to have at least a partial change of heart in the end, getting one last fight scene, a dramatic death, and redemption as he becomes one with the Force. Still, the film asked questions about the nature of Jedi, the Force, and what the role of both should be in the lives of the billions of beings throughout the galaxy.

The Acolyte Asks Questions That Naturally Arise From What Came Before

The Acolyte received favorable reviews from critics but holds a poor fan score on Rotten Tomatoes.

Some fans have suggested that it’s the victim of a review-bombing campaign.

In addition to the Jedi controversy, it also raised eyebrows by including Master Ki-Adi Mundi.

Since the sequel trilogy wrapped up, writers in the Star Wars franchise have continued to touch on these themes. Ahsoka saw the titular character struggling with her own feelings of uncertainty about her service in the Clone Wars. Obi-Wan Kenobi features a protagonist who is scarred mentally and emotionally, also struggling with questions about who he is and how to be a Jedi. Far from breaking Star Wars’ canon, The Acolyte is simply a continuation of these shows and everything else that came before.

The Acolyte may take things slightly further and draw the Jedi into darker deeds, but it clearly builds on what came before. The prequels raised the question of how the Jedi fit into the Republic and hinted that they were a power that operated outside the official, democratic system. The Acolyte merely makes this more explicit. It highlights the Order’s ambiguous status as an independent, and often secretive, organization and invites viewers to consider how such a group should operate in a democracy.

The Last Jedi and some material from the Expanded Universe asked whether the Jedi represent the one true way to connect with the Force. The Acolyte carries this forward by presenting a group who see the Force in their own unique way and putting them in conflict with the Jedi. The series may have represented a big step forward with regard to these themes, but it hardly invents them out of nowhere.

The Canon is Always Evolving

Disney has already upset some fans by de-canonizing much of the Expanded Universe.

Many of these elements have since been added back in through a new show or movie.

Some fan favorites, like Mara Jade and Kyle Katarn, remain in limbo.

Long-running franchises often struggle with building on and expanding the setting while simultaneously keeping the canon straight and pleasing the fans. Star Wars is no different. It would be a mistake, however, to think that Disney’s current struggles in the galaxy far, far away are anything new. This particular controversy, in particular, has been brewing for some time.

When The Phantom Menace released in 1999, lots of fans were upset with it and the two movies that followed. There were accusations that it ruined Anakin’s backstory, contradicted things Yoda and Obi-Wan said in the original trilogy, and a myriad of other things. Of course, lots of fans loved, and continue to love, the prequels and defended them against those accusations. Now, some of those fans are lodging similar complaints against Disney’s entries in the Star Wars saga.

This doesn’t necessarily make The Acolyte a good show or a bad show. That will be something for each fan and critic to decide for themselves. The fact remains, however, that criticism of the new series on the basis of how it interprets the canon is misplaced. Star Wars has been evolving since the 1970s and the specific threads that The Acolyte has been pulling at have been developing since the prequels.