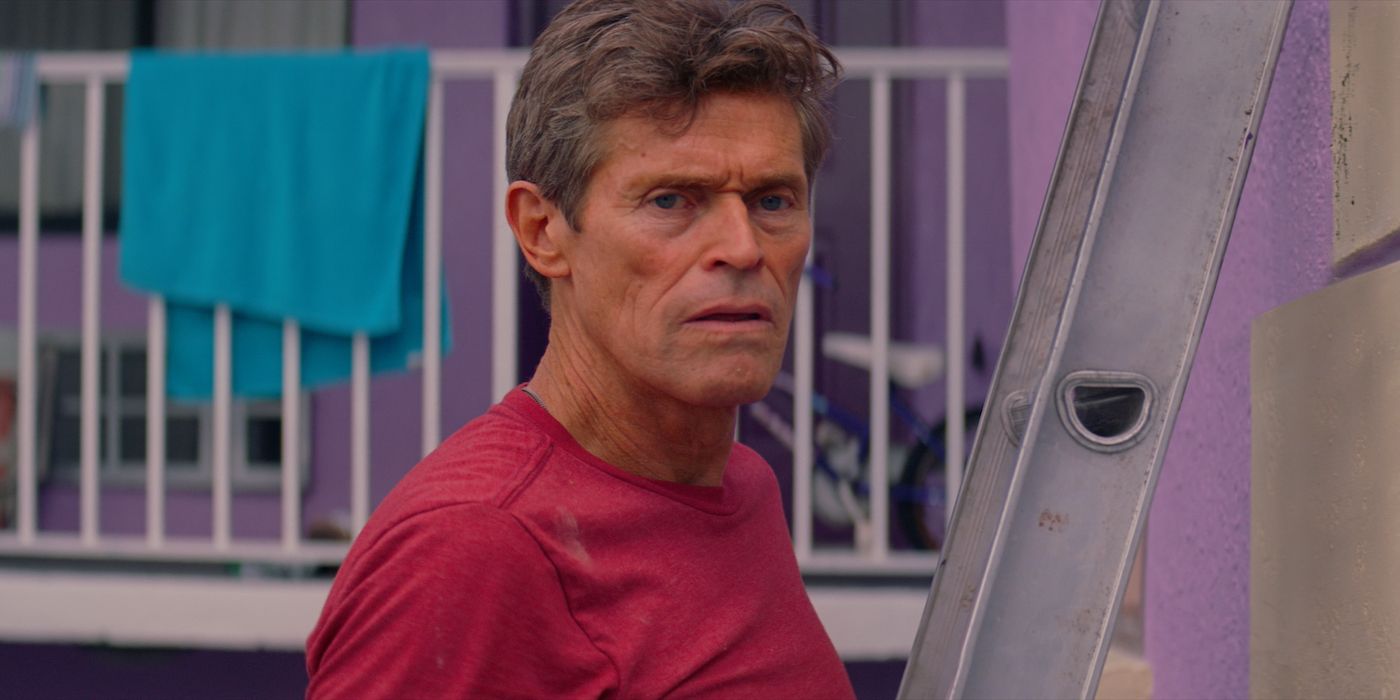

The actor’s Oscar-nominated performance is a far cry from his iconic heavies and oddballs.

The most assuring sign is when Willem Dafoe shows up in a film. One of the best actors working today, Dafoe has never mailed in a performance, no matter the genre, scale, or quality of film. This is not to say that the 4-time Oscar-nominated actor carries himself with a pretentious display of a manic and tortured artist. Every interview and off-camera sighting of his demonstrates him as an amicable and humble star. Despite his wholehearted off-screen persona, Dafoe has made a name for himself playing perverse and ominous characters, oftentimes as a villain, in films for the last 40 years. One role of his, as the well-to-do and vigilant motel manager in The Florida Project, suggests that his warmer side is untapped.

Willem Dafoe Has a History of Playing Oddballs and Villains

Throughout his prolific career as a screen actor that continues today – including his acclaimed performance in Yorgos Lanthimos‘ Poor Things – Dafoe specialized in playing heavies and eccentric oddballs. He emerged in the 1980s as the antagonist of William Friedkin‘s propulsive cat-and-mouse thriller, To Live and Die in L.A., and Walter Hill‘s neo-noir crime thriller, Streets of Fire. Oliver Stone and Martin Scorsese extracted a more soulful side to his screen presence while retaining his alluring mystique in Platoon and The Last Temptation of Christ, respectively. An actor of his prestige held no qualms about playing a comic book supervillain in Sam Raimi‘s Spider-Man. Because his turn as the Green Goblin was so iconic, there was no question that he needed to return to the role in Spider-Man: No Way Home. Dafoe, who began his career in 1975, becoming a mainstay in the films of Wes Anderson, Robert Eggers, and Paul Schrader, carries a youthful energy to the screen in his vast array of supporting performances.

The Florida Project, the film by indie visionarySean Baker, is a slice-of-life narrative following the summer adventures of a six-year-old girl, Moonee (Brooklynn Kimberly Prince), as she relishes in the delight and innocence of life in a budget motel in Kissimmee, Florida, on the outskirts of Walt Disney World. Moonee’s day-to-day romp with her friends is juxtaposed with the sobering reality of her unemployed single mother, Halley (Bria Vinaite), who encounters the hardships of an impoverished lifestyle. The Florida Project verges on documentary in its plotless structure and raw depiction of a disregarded pocket of society. Baker’s film probes the viewer to reflect on America’s class struggle through an objective and nonjudgmental perspective. The camera moves with the ease of one of Robert Altman‘s expansive, eclectic character studies.

Willem Dafoe is the Heart of Sean Baker’s ‘The Florida Project’

Sitting at the linchpin of the story is Willem Dafoe as Bobby Hicks, the manager of the film’s subject motel, Magic Castle, which is a place of permanent hospitality for most of the residents. His weight and gravitas are notably present in this film, as most of The Florida Project‘s cast were not professional actors. In a seamless effort, Dafoe, who received an Oscar nomination for his performance, conceals his fame and becomes one with Baker’s environment. The actor stated in a GQ interview that he viewed the film as “an opportunity to not be an actor.” He was motivated by Baker’s blend of fiction and real life, as the cast and crew were learning about this particular environment during production. Even for the most skilled actors, stripping away the artifice of performance to play an “authentic” person naturally exhibits a performance. Attentive viewers can identify when an actor is trying to be “real,” but Dafoe’s transformation into an embodiment of cinéma vérité is exceptional.

A young Floridian mother and daughter struggle to keep a roof over their heads in Baker’s follow-up to the celebrated ‘Tangerine’.

Along with being the manager of this budget motel outside the kingdom where dreams are made, Bobby serves as a guardian for Moonee and her friends, Scooty (Christopher Rivera) and Dicky (Aiden Malik), who lack proper parental oversight. This is not to suggest that Bobby’s relationship with the children is wholly amicable, as they provide a litany of headaches for the manager, such as when the kids shut off the motel’s electricity, or when they are harassing tourists. Regardless, he, along with the audience, sympathizes with Moonee and her friends, as they are troubled. This is why, when he’s not busy crunching the numbers of the motel’s finances or enlisting maintenance support from his son, Jack (Caleb Landry Jones), he is chasing away drug dealers and the solicitation of sex work on his property.

This character dynamic of an upstanding adult figure looking out for a group of haphazard kids invites the possibility of hokey or condescending storytelling, but Baker’s voice is too mature and nuanced to fall for clichéd traps. Dafoe’s magnetic screen presence ties the entire picture together. Striking a balance between sympathy and sternness in his depiction of the motel manager, Dafoe’s three-dimensional performance drives The Florida Project. Even if the character is presented in a cut-and-dry archetype, the sturdy adult mentor for aimless kids, watching Bobby attempt to maintain order by running his business and protecting the kids is captivating, especially through Baker’s expressive camera. He’s not perfect either, as his distant relationship with his son is a void in his life.

Willem Dafoe’s Humanism and Vulnerability in ‘The Florida Project’ is Untapped

Dafoe’s ability to hold the screen, such as when the camera tracks Bobby walking along the parking lot as he announces that the power is back on, conveys his endearing humanism. In this scene, Baker immediately establishes that helping people is his calling card. He’ll express frustration while completing menial tasks and managing various nuisances, but ultimately, he takes pleasure in hearing gratitude from residents. Bobby thwarting a stranger, suggested by the film as a child predator, from harming the kids on the lawn conveys his undying guardianship. Bobby is also shown to be exhausted. While smoking and looking out across the parking lot, his internal sadness resonates. The audience is exposed to a limited amount of information regarding his background and personal life, yet you feel that he deserves something better.

Because of his vulnerability, Bobby can hardly be categorized as an uncompromising, hard-nosed dictator, even when we see him evict residents or diligently enforce motel policy. An exchange between Bobby and Halley, which shows the latter paying her rent, succinctly portrays him as a stringent but forgiving figure. Halley is insulted by Bobby counting the money that she handed him moments ago, as it insinuates that she is ripping him off. While Bobby continues counting the money, he is affected by Halley’s affronted response. Bobby expects human decency to go both ways and wants to show that he is not her enemy.

Willem Dafoe’s pervasive benevolence and desire to make the best out of everything in The Florida Project unlocks an untapped source of humanism from the actor. The role transcends the notion that Dafoe’s participation in the film was a mere demonstration of casting against type, as he transfers his innate charm and gravitas to a funny and heartbreaking story. While he is routinely excellent in these parts, Dafoe is frequently cast as a character with sinister undertones. You wouldn’t want his maniacal sailor in The Lighthouse or his mad scientist in Poor Things as your caretaker at a motel. If he’s not a forbidding presence, then he carries an unknowable quality, which helps him give a mesmerizing performance as Jesus in The Last Temptation of Christ or any film as a member of the unofficial Wes Anderson Stock Company. Dafoe’s previous body of work suggests that he is incapable of the vulnerability reflected in The Florida Project. In the end, Sean Baker’s film proves that he is equipped to play more quiet roles, such as Bobby Hicks.

The Florida Project is available to stream on Netflix in the U.S.