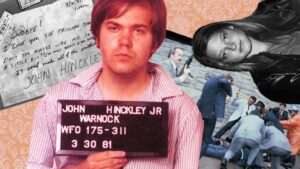

On March 30, 1981, John Hinckley Jr. fired multiple shots at President Ronald Reagan as he exited Washington, D.C.’s Hilton Hotel following a speech at an AFL-CIO conference. Shooting wildly, the would-be assassin struck four individuals: Reagan (via a bullet that ricocheted off his limo); police officer Thomas Delahanty; Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy; and White House Press Secretary James Brady. More stunning than this attempted crime—or the fact that the injured all survived the attack—was Hinckley’s motivation, as it soon became public that he’d tried to execute the commander-in-chief in order to impress actress Jodie Foster, with whom he’d become obsessed thanks to Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. When Hinckley was subsequently found not guilty by reason of insanity, outrage ensued, although he remained in psychiatric care for the next 30 years.

Released from Washington, D.C.’s St. Elizabeths Hospital in 2022, Hinckley is now a free man, and he sits down to present “the untold truth in his own words” in Hinckley: I Shot the President. Director Neil McGregor’s documentary portrait of this infamous individual, however, has almost nothing to tell that hasn’t already been told countless times before. Worse, it omits as much as it reveals, fixating so doggedly on its subject that it fails to dig into the various pertinent questions and dilemmas raised by his tale.

Winter Skin Care Tips That Will Help You Stay Healthy During The Upcoming Cold Months!

“I shot the President of the United States in 1981, and wounded three people,” states the 69-year-old Hinckley at the outset of McGregor’s film, and that bluntness epitomizes everything else he articulates for the ensuing hour and a half. In a series of interviews that are marked by their lack of revelations and energy, Hinckley recounts his life story, beginning in Dallas, where he lived with a “tight-knit” family and experienced a “typical childhood” that was marked by “no real traumas.” Hinckley admits that he had few friends throughout school and that his isolation was “something that hangs over you for 24 hours a day.” The lone thing that elevated him above the persistent gloom was music, and he cites The Beatles’ arrival on U.S. shores (and their legendary appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show) as a formative moment.

To follow in “idol” John Lennon’s footsteps, Hinckley moved to New York City in 1976, only to last one single night before fleeing the scary and overwhelming metropolis for home. In reaction to this failure, he decided to give Los Angeles a chance, and he survived for a stretch off the proceeds earned from selling his car, wandering about the sleazier parts of Hollywood, visiting porn shops and the avenues frequented by prostitutes.

No surprise, then, that this disaffected loner took to Taxi Driver and, in particular, to its estranged and unhinged protagonist Travis Bickle (played by Robert De Niro). Before long, Hinckley was repeatedly watching the film (he guesses he saw it 15 times in theaters) and emulating Bickle, from drinking peach schnapps to wearing an army jacket. Moreover, he became consumed with the idea of saving actress Jodie Foster in the same way that Bickle rescues her child-prostitute character Iris at movie’s conclusion.

Hinckley matter-of-factly confesses that he “got fixated on her, obsessed with her,” yet he can’t really pinpoint why she struck such a chord, other than that there was something about her that he found “mesmerizing.”

Such is the insight of Hinckley, whose sole talking head is Hinckley himself. By confining itself to its center of attention, McGregor’s documentary gets a first-hand account of his ordeal and headspace at the expense of any outside perspective that might illuminate his behavior, motives, or condition. Hinckley isn’t verbose and many of his comments sound like platitudes that have been rehearsed ad nauseam, and their effect is to obscure the thornier aspects of his saga. To wit: Hinckley often mentions his “mental illness” without ever specifically defining it, which renders it an abstract—and thus less dangerous-seeming—force.

Due to his “unsound mind,” Hinckley became increasingly preoccupied with Foster, whom he followed to New Haven, Connecticut in 1980 once she began studying at Yale. Hinckley boasts snippets of audio recordings of his multiple phone calls to the teenage actress, and in a startling anecdote, Hinckley remembers spotting her on the campus, approaching her, and then chickening out and concealing his true identity by simply asking her for directions to the library. Desperate to make a grand gesture that would bring them together forever, Hinckley bought a gun and devised a plan to hijack a plane out of Nashville—his thinking being that he’d demand she be brought to him so they could fly away as a couple—but he was arrested by airport security before he could carry out his harebrained scheme. Afterwards, he decided that murdering the president would suitably impress her, ultimately leading to his unsuccessful assassination attempt.

Hinckley complements Hinckley’s commentary with archival footage, photos, letters, and news reports, at least some of which plays as padding. What’s missing throughout is any analysis or critique of Hinckley’s assertions and actions. Instead of investigating the origins of Hinckley’s mental illness, how it went untreated for so long, and the means by which he supposedly overcame it—hence his release from St. Elizabeths—the film spends time allowing Hinckley to talk about his music, art, and desire to move on with his life. It’s understandable that the wannabe-singer-songwriter doesn’t want to be remembered for trying to kill Reagan, yet that’s unquestionably the only reason he will be, and granting him a vehicle to sympathetically ask that everyone give him a break seems simultaneously offensive and pointless.

At its conclusion, Hinckley depicts its subject sitting on his couch watching footage of the recent July 13, 2024, attempt on the life of Donald Trump. However, from the timing of this feature’s VOD debut, to Hinckley’s unresponsiveness to this material, it’s clear that it’s a manufactured scene; director McGregor appears to have digitally superimposed the Trump clip onto Hinckley’s screen. That Hinckley and Trump’s would-be assassin Thomas Matthew Crooks are likeminded creatures would certainly be a relevant theme to explore in an affair such as this. As it stands, though, this final bid for timeliness is just as flat as the rest of this non-fiction venture.