Newly uncovered legal documents show how the old NDA negotiated between the former Fox News host and his producer still binds them both.

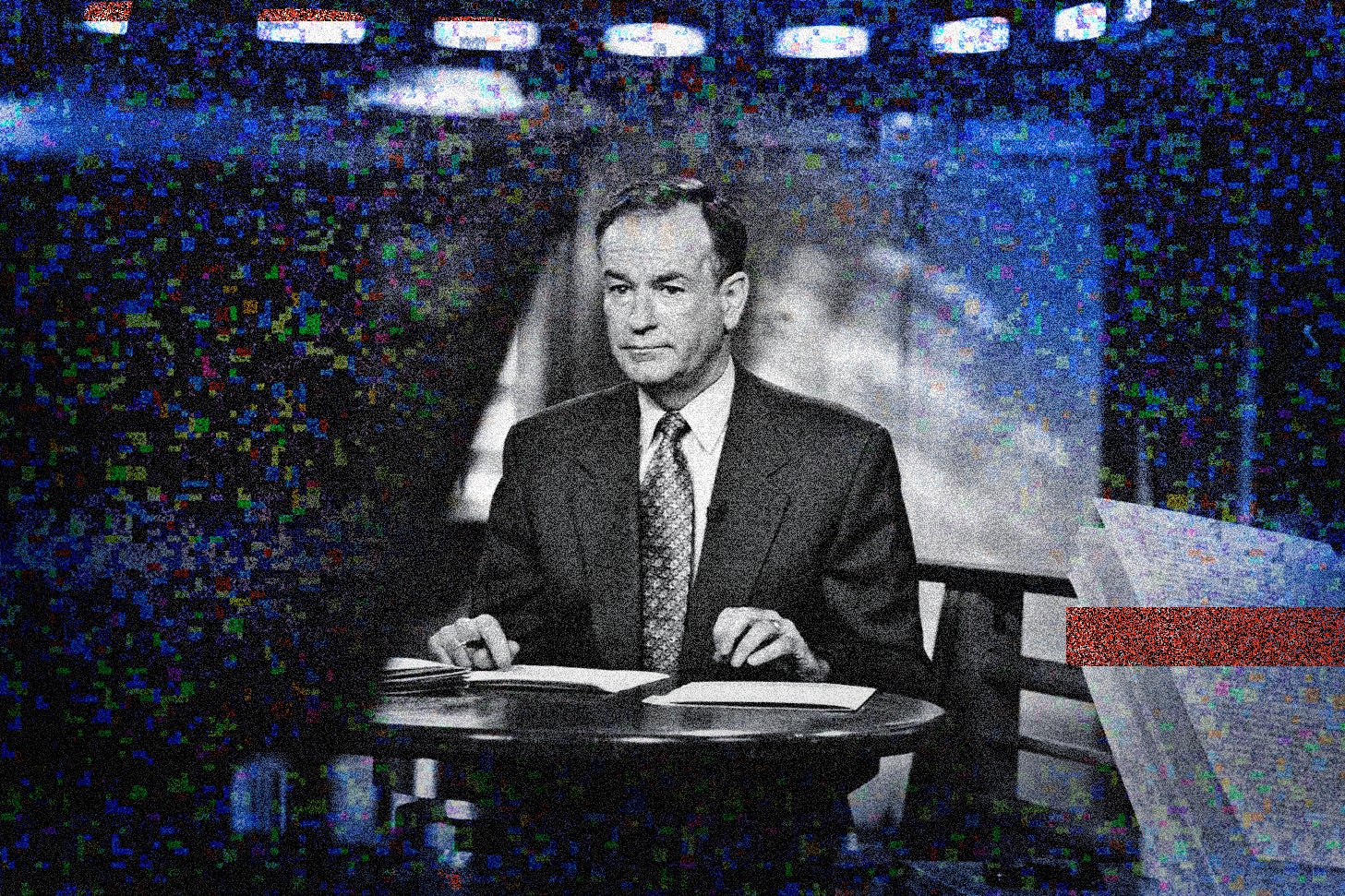

All the way back in 2004, Andrea Mackris became the first woman to accuse Fox News host Bill O’Reilly of sexual harassment. Her story did not gain her much support: Two decades ago, and long before #MeToo, the public seemed more primed to joke about O’Reilly’s lasciviousness than to empathize with Mackris, a producer on The O’Reilly Factor. The specifics of the alleged harassment didn’t help either—somewhat infamously, O’Reilly imagined rubbing her “with the falafel thing” when he had meant to say loofah. Critics delighted in the hypocrisy of a family-values conservative cheating on his wife in such a sordid way but did not stop to ponder what it must have been like to actually work for this guy.

Her accusations came to light only because Mackris and O’Reilly filed lawsuits against each other, and the filings were both posted on the website the Smoking Gun. Certain details were printed verbatim from the transcripts of recordings Mackris had made that became public via the lawsuits. They were both salacious and memorable, in a way that lent credibility to Mackris’ claims and provided fodder for comedians and bloggers, like the loofah thing. But the settlements that Mackris and O’Reilly eventually signed soon prohibited them both from speaking about the subject.

Which is why it must have been such a relief when, in the summer of 2021, Mackris seemed liberated enough by the #MeToo movement to start to talk about what had happened to her. It was a few years after Harvey Weinstein’s fallout—it seemed that the shift in power away from abusers to accusers was no blip, that the women who took down powerful men still had the public on their side. More critically, by that point, O’Reilly had long been ousted from his job, after several more women levied similar accusations in 2017. The reasons to doubt her story seemed seriously reduced.

Mackris kicked off her campaign with a tell-all interview with the Daily Beast, for a story titled “Bill O’Reilly’s Accuser Finally Breaks Her Silence.” A month later, the Daily Beast dropped a podcast interview with Mackris, diving into the forces that protected O’Reilly and her “forced” NDA that she was now willing to breach. She next made plans to go on The View. Then, suddenly, with no further statement, she went quiet.

We now know why: According to previously unreported legal documents surfaced by my colleague Josh Levin and me, O’Reilly launched a legal challenge against Mackris over her going public because, as she herself said, doing so violated her original NDA. The results of the confidential arbitration that followed were unsealed this past March.

That arbitration panel found that both parties were guilty of breaking their agreements. Mackris and O’Reilly each had to pay nearly $100,000 for the cost of their legal battle, with the power of the NDA reasserted over both of them.

The end result shows the ways the system is still rigged toward the rich and powerful. In some ways, that’s because of the obvious reason: The legal costs were likely nothing to O’Reilly, but, based on mentions of Mackris’ financial strain in the filings, they were likely significant for Mackris. But more interesting is what was revealed about the original NDA and legal agreement that Mackris signed when she negotiated this settlement 20 years ago. In a declaration publicly filed in court in 2021, Mackris says that she signed the original NDA in tears and under pressure from attorneys who told her how unsympathetic she would seem to the world. Not only that, the NDA itself is a fascinating thing to consider. Among other oddities, it required Mackris to turn over the recordings she had of O’Reilly and bound her to lie about their validity if ever confronted with them, an odd element that attorneys for the National Women’s Law Center say is highly unusual. “We do a lot of advocacy against use of NDA agreements in sex harassment,” said Jennifer Mondino, the senior director of the NWLC’s Time’s Up Legal Defense Fund. “I can’t think of any one that has language like this, where it’s telling people to lie. That seems like a wild thing for lawyers, on both sides, to be saying.”

It’s an indication that society may have changed with regard to NDAs, sexual harassment, and Bill O’Reilly’s reputation, but the legal documents made before #MeToo are as binding as ever.

Andrea Mackris’ time at Fox began to sour when she and her fiancé broke up. It was May 2002, close to two years into her time as an associate producer for The O’Reilly Factor, and Mackris suddenly found herself in need of a raise to afford her rent. She asked a Fox executive for help, and he spoke to O’Reilly; O’Reilly then invited Mackris to dinner.

Mackris had traveled with O’Reilly before, without incident. But according to her original sexual harassment lawsuit, at that dinner, O’Reilly suddenly began talking about his masturbation and his past sexual escapades. He urged Mackris to use a vibrator “to blow off steam”; she would later tell the Daily Beast that he finished the dinner by saying, “Stick with me and you’ll go far.”

According to the affidavit given during that 2021 legal dispute, she says O’Reilly continued the harassment. He tried to ask her and a friend for a threesome; repeatedly asked her to engage in phone sex; shared sexual fantasies about her; and masturbated on the phone while speaking with her. At one dinner, Mackris testified, she warned him that she knew he harassed other women too and he should be careful. “Mr. O’Reilly vehemently responded with threats to the effect: ‘If any woman ever breathed a word I’ll make her pay so dearly that she’ll wish she’d never been born,’ ” her filing says. “ ‘I’ll take her through the mud, bring up things in her life and make her so miserable that she’ll be destroyed. And besides, she wouldn’t be able to afford the lawyers I can or endure it financially as long as I can. And nobody would believe her, it’d be her word against mine and who are they going to believe?’ ” At the time these accusations became public, and every time they have come up since, O’Reilly has denied any wrongdoing.

To hear more about this time at Fox, listen to the season finale of Slow Burn: The Rise of Fox News.

The problem for Mackris is that this all allegedly happened before there was a real playbook for how to handle it. Plus, Mackris loved her job, and O’Reilly was still a highly respected figure in broadcast media. So instead of quitting or taking other, more drastic action, she says, she attempted to sidestep his advances, insisting, in her legal filings, that she repeatedly asked O’Reilly to stop talking about sex. O’Reilly, she alleges, ignored her.

It continued for years, she claims. Mackris recorded “many” of these calls, she claimed, in her 2021 affidavit. For six months in 2004, she left for CNN, but she didn’t like the workplace and returned to Fox. Until August of that year, O’Reilly treated Mackris professionally; then, she said, he started up again, calling her on the phone and masturbating while he spoke to her. The final straw for Mackris was an incident in September in which he called and relayed a mutual-masturbation fantasy, ending with a promise that “next time, you’ll come up to my hotel room and we’ll make this happen.” Again, O’Reilly denies doing any of this.

“Once again, like every other time, I asked him why he continued to do this when I only ever said ‘No’ and ‘Please stop’ and ‘You’re my boss,’ ” she recalled to the Daily Beast. “Instead, he said, ‘I know, but I’m going to make you play.’ Here was my boss, a man who held my career and future in his hands, acknowledging that he knew I’d never consented but he didn’t care.”

After that call, she hired lawyers, who sent a sexual harassment complaint to Fox. But before Mackris could go any further, O’Reilly hit her with a lawsuit, alleging that she and her lawyer were trying to extort him out of $60 million in hush money.

“This is the single most evil thing I have ever experienced, and I have seen a lot,” he said on his show that day.

Within 24 hours, she filed a sexual harassment lawsuit against O’Reilly and Fox.

The information contained in those suits was ultimately published, and widely consumed. But the focus was more on mockery of O’Reilly than on support for Mackris. Some doubted her motives; others seemed to question how bothered by it she had really been. In his column in the Washington Post, Richard Cohen argued that Mackris either lacked common sense or was playing O’Reilly in order to get better assignments and pay. She had, he wrote, undermined her own victimhood by going to dinner with him, by going up to O’Reilly’s hotel room to watch a presidential press conference, by returning to Fox after her stint at CNN. “I almost pity O’Reilly,” he wrote. “If he did it, it is wrong—just plain wrong. But it is also wrong for a woman to be even a bit complicit and then act as if she played no role whatsoever in the oldest game known to mankind. [S]he screamed for help a bit late in the game.”

The New York Post ran with two stories that portrayed Mackris as unstable, cruel, entitled, and sexually aggressive. O’Reilly, meanwhile, had begun his own public relations campaign, portraying himself as a victim of a politically motivated attack by Mackris’ attorney, who had donated to Democrats. “There comes a time when enough is enough,” he proclaimed on his own show the night of his lawsuit. The next day, he went on Live With Regis and Kelly to spell out his extortion accusations. “I knew I would perhaps ruin my career,” he said of his lawsuit. “If I have to go down, I’m willing to do it.”

On Oct. 28, 2004, the news broke that O’Reilly and Mackris had settled. No details emerged, but O’Reilly’s lawyers put out a statement declaring that everyone involved regretted the pain caused by the litigation and agreed that there had been “no wrongdoing whatsoever” by anyone.

On air, O’Reilly told his audience, “This brutal ordeal is now officially over, and I will never speak of it again. This matter has caused enormous pain, but I had to protect my family, and I did. All I can say to you is please do not believe everything you hear and read.”

Later, thanks to reporting in the New York Times, the public would learn what had happened: O’Reilly had agreed to pay Mackris $9 million, $3 million of which would go to her lawyers as a contingency fee. Mackris agreed to leave Fox. Both parties agreed to sign a nondisclosure agreement, binding them to not speak publicly on the topic.

It seemed to be a standard series of events. But in April 2018, in a related legal filing, the original agreement was made public, revealing a few strange things.

For one, Mackris had been required to turn over all her audio recordings, diaries, and anything else that counted as evidence to O’Reilly’s lawyers to be destroyed. Mackris and her lawyers had to agree that, should any such evidence ever somehow emerge publicly, Mackris was legally bound to lie about their validity. Here’s the exact language: “It is expressly agreed that, should any Materials become public by any means including through third parties after the date of this Agreement, all parties will disclaim them as counterfeit or forgeries.”

Then there was the agreement by her lawyers to not provide legal help to anyone suing O’Reilly and to instead “provide legal advice to O’Reilly regarding sexual harassment matters.” The easiest way to explain this is to say that it was bizarre and baffling, but as the Times noted at the time, it was “considered unethical in the legal community.” As Dahlia Lithwick wrote, also at the time, “It’s hard to read that as anything but Mackris’ lawyer changing sides and joining forces with O’Reilly as a condition of the settlement agreement.” And a lawyer for Mackris in 2018, looking back at her original agreement, called the arrangement “profoundly unethical,” arguing that the lawyer switch “left Ms. Mackris virtually without legal counsel.” Mackris had to agree to waive any conflict-of-interest claims arising from this particular arrangement.

Combine that arrangement with the destruction of the tapes and the full silencing of Mackris (only O’Reilly was allowed to relay, to his millions of viewers, a statement “consistent with” the agreed-upon public comment drafted by lawyers) and it seems abundantly clear that O’Reilly came out of the agreement with a better public-facing resolution than Mackris did.

But the strangest element was this: The mediator for the 2004 settlement, it turned out, was Marc Kasowitz. Kasowitz is now known for representing Donald Trump, but more relevantly for this case, Kasowitz would go on to represent O’Reilly against later sexual harassment charges.

On April 1, 2017, the Times’ Emily Steel and Michael S. Schmidt published an investigation that found that five women working for Fox had entered settlements with O’Reilly over sexual misconduct claims. The Times reported that Fox News and O’Reilly had hired a public relations firm to help him control the narrative and a private investigator (Bo Dietl, who was also a Fox News contributor) to dig up dirt on Mackris. “The goal was to depict her as a promiscuous woman, deeply in debt, who was trying to shake down Mr. O’Reilly,” the Times reported. Mackris was photographed in the article but didn’t speak about the details of the case; she instead told them about PTSD and identity struggles after being forced out of the company—and out of the industry, as she sees it.

O’Reilly responded to the article by going on the offensive, saying that the women who accused him were politically motivated extortionists. On the Today show, speaking with Matt Lauer (another man later fired for sexual misconduct allegations), he described the allegations as “a hit job, a political and financial hit job.” On his own podcast, he blamed “smear merchants” and said, “My enemies who want to silence me have made my life extremely difficult.” He told Sean Hannity that he was “conducting an investigation” that would clear his name and “expose the whole thing.” He told New York Times reporters that he could prove that it was all “bullshit.”

He was represented during this time by Kasowitz. And Kasowitz would go on the record as saying he had proof that the women’s stories had been invented for political reasons. “Bill O’Reilly has been subjected to a brutal campaign of character assassination unprecedented in post-McCarthyist America,” Kasowitz said in a 2017 statement. “This law firm has uncovered evidence that the smear campaign is being orchestrated by far-left organizations bent on destroying Bill O’Reilly for political and financial reasons. That evidence will be put forth shortly and it is irrefutable.” If that proof was shared anywhere, it never surfaced publicly. And it wasn’t enough to overrule the women’s claims.

For Mackris, this was galling. After she learned that other women who claimed they had been harassed by O’Reilly had banded together to say that he had broken the terms of their agreements by talking about them and had also defamed them in what he said, Mackris joined the suit. This effort wouldn’t go anywhere—the judge eventually decided that the women weren’t singled out enough by O’Reilly’s vague complaints for it to count as defamation—but it did lead to the unsealing of the original settlements between O’Reilly and his accusers. When the public learned about the particularities of Mackris’ deal in April 2018, the #MeToo movement had changed the public’s perception of NDAs as well.

Perhaps it was that popular support that gave Mackris the confidence to speak out in 2021, after her last hopes of getting a jury trial for her complaints were quashed. In July, the Daily Beast ran the interview with Mackris in which she recounted the harassment, as well as the story of the 2004 NDA. In her telling, she had been coerced and her lawyers had pressured her to take the money.

There is no question that sharing the story of the NDA violated the terms of the NDA. It had stipulated that “the nature and terms of this settlement and Agreement, including the existence of this Agreement and the fact and amount of any payments are to remain completely confidential.”

For the same reasons, Mackris couldn’t talk to Slate for this article. But during the brief moment that she was willing to talk, she told the Daily Beast that she had decided to take on the legal risk anyway—that she felt it was the only way to regain power over her life.

“It’s taken time to face the fact that there isn’t any ‘moving on’ while I am still bound to lie for Bill,” she told the Daily Beast. “What more can attorneys and henchmen and a corporation’s continued denial do to me that they haven’t already done?”

Turns out they could continue to deny her even that. The day before Mackris planned to go on The View, O’Reilly’s lawyers served her with a restraining order. The public would not hear directly from Mackris again.

Even though Mackris can’t tell us what happened during this period, we know, from her court filings and from her conversations with the Daily Beast, that she was aware she was taking a risk in speaking out about O’Reilly.

“If I have to pay a breach, it’s less than the cost of the past 17 years,” she said in a Daily Beast podcast from July 2021. “I’ll tell you that I welcome the risk because this is intolerable.”

Mackris has said the harassment, the litigation, and the aftermath all took a toll on her mental health. In speaking to the Daily Beast, she emphasized how hard it had been to feel suddenly frozen out of the world of broadcast news media, derailed from a promising career that had been central to her identity. There was also the unsettling amount of attention her case drew: According to the newly unsealed arbitration testimony, the period right after the publication of the 2017 Times article had been particularly miserable for Mackris. She said she became afraid of “intruders and others who might wish to cause her harm.” In documents that were referenced but not unsealed, she spoke of the return of her PTSD.

It’s hard to see how Mackris envisioned it ending in anything but a ruling against her. The NDA specified that she could not discuss or “disclose, directly or indirectly, by expression, implication or inference, any information concerning” the agreement, its terms, and its underlying claims. But in the recent round of litigation, Mackris contended that she had real reason to think she could breach the NDA: O’Reilly, she asserted, had nullified the NDA by himself speaking out against his accusers in 2017.

This wasn’t an argument any legal experts Slate spoke with thought was particularly viable. But it’s possible that Mackris really believed this. After all, was it fair that one party could share his opinions on the matter while the other party remained muzzled?

Also, the laws around NDAs had changed by that point. In 2018 the New York state Legislature passed a law banning NDAs related to sexual harassment, unless the victim wanted one. And even in the latter scenario, an alleged victim was to be given 21 days to consider whether to sign such an agreement, with seven more days to change their mind. It’s clear Mackris was not given three weeks to consider the NDA. And confidentiality was clearly not her preference.

Miriam Clark, a labor and employment lawyer at the New York firm Ritz Clark & Ben-Asher, said it was possible to make the argument that this law could retroactively apply to old agreements but that it wasn’t likely to succeed.

Similarly, Clark said, an attorney could try to nullify an old agreement using a 2023 decision from the National Labor Relations Board that related to disparagement clauses in severance agreements. According to Clark, courts still need to work out whether the terms can affect agreements made over sexual harassment claims and involving high-salary, non-union employees.

There’s some reason to think that in the future, things could change for women like Mackris who are tied to old agreements drafted before these laws addressed the inherent power imbalances. Mackris’ 2004 NDA almost certainly wouldn’t come about today. But for now, she is still bound by it.

Josh Levin contributed reporting.