It may not seem that Jodie Foster — Yale graduate, two-time Academy Award winner, director, actress, and producer — shares much in common with the average person, but at least this much is true: She has felt like a failure for much of her life, too. That’s … sort of reassuring?

Because of the political moment in which it’s landing, the new movie Money Monster — about a cheesy TV financial guru and the viewer who takes him hostage — will almost surely be seen as a parable of income inequality and a rigged economy. Which, in large part, it is.

But to its director, Jodie Foster, it covers terrain more intimate than that, and more personal. It’s a meditation on failure: how keenly people fear it, what they do when confronted with it. Its two main characters, captor and captive, inhabit the same purgatory. They’re coming to terms with their own inadequacy.

“Failure is a big one for me — people in spiritual crisis, in a moment in life of total self-hatred,” Foster told me recently, explaining how the movie, to be released May 13, connects to her.

Does she often think of herself as a failure?

“Oh yeah,” she said. “Oh my God, yeah. If Mother Teresa is propelled to do good works because she believes in God, I am propelled to do good works because of how bad I feel about myself. It’s the first place I go. ‘Oh, what did I do wrong?’”

This is not the direction in which you expect a conversation with a two-time Oscar winner to turn. But as guarded as so many decades in the spotlight have made Foster, there’s also something naked about her, a soul-searching too fervent to stay hidden.

You see it in her best performances. You saw it at the Golden Globes in 2013, when she accepted an honorary award with a raw, rambling speech that set the Internet ablaze: Had she just come out of the closet? Had she even been in the closet?

She was asking at once to be understood and to be left alone, still searching all these years later for a resolution to the contradiction of celebrity, and her remarks were so messy in their way that I was stunned when she told me that she’d scripted them carefully in advance.

“Every word,” she said, adding that she even had them put on a teleprompter. “I didn’t want to get it wrong.”

But what precisely was she trying to get right? The world was fixated on her allusions to her private life. She was focused on an announcement about her professional one: On the far side of 50, she was pivoting toward less glamorous work behind the scenes.

She hasn’t taken a new acting assignment since, instead concentrating on directing. Money Monster is her fourth big-screen effort along those lines, after Little Man Tate (1991), Home for the Holidays (1995) and The Beaver (2011), and it’s by far the most ambitious, a New York City thriller with SWAT teams, explosives, George Clooney and Julia Roberts.

Clooney is the financial guru, who loosely evokes Jim Cramer, the host of the CNBC cable show Mad Money. Roberts is his producer, who’s in his ear throughout the hostage crisis, talking him through it, as steady as he is spastic. (The captor is played by Jack O’Connell.)

One striking aspect of the movie is how large Roberts’ character looms, and I asked Foster if that would have been the case in a male director’s hands. She said that she hadn’t thought about that, but, in fact, many of the screenplay revisions that she requested involved fleshing out that role.

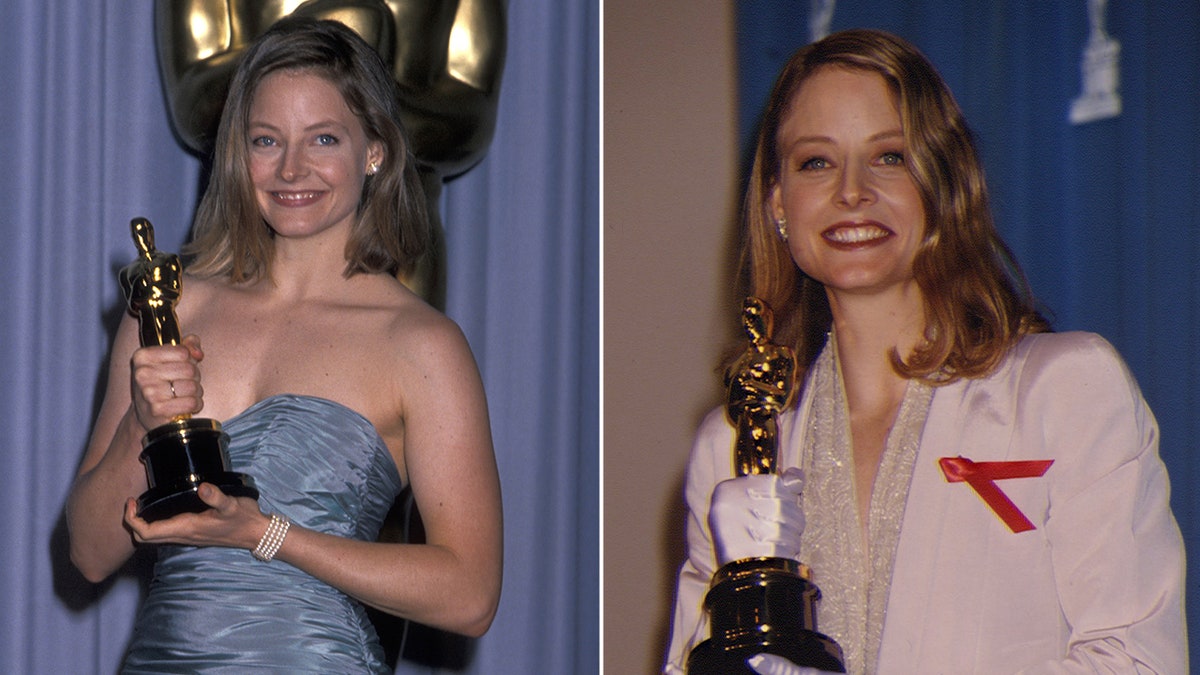

Strong women are her trademark as a performer, the thread running through The Accused (her first Oscar for best actress), The Silence of the Lambs (her second), Panic Room, Flightplan, The Brave One and more.

But not just strong women: women who don’t turn to a man in the clutch; women whose strength is inseparable from the walls they’ve built around themselves. They’re “solitary characters who don’t have mothers and fathers and boyfriends,” she told me, and they demonstrate her desire, when acting, “to have an experience that’s all mine, and I don’t really want to share it.”

“Yet I’m totally desperate to communicate it to you,” she said. “It’s a really weird dichotomy. And I think that’s me in life.”

She sat on a couch, legs curled under her and shoes kicked off, in an office here on the lot of Sony Pictures, which is distributing Money Monster. I’d last seen her in downtown Manhattan months earlier, when she was shooting a crucial scene and when she described, within minutes of our meeting, how powerfully the Clooney part spoke to her.

“He’s just a guy on TV, but he’s imbued with this sense of power,” she said, adding that he’s forced to ask questions that she has asked herself: “Am I real? Am I a sellout? Is all of this real?”

She meant the adulation that comes with fame, which she achieved early. The year she turned 14, she had five movies released, including Freaky Friday, Bugsy Malone and Taxi Driver, in which her precocious turn as an underage prostitute earned her an Academy Award nomination for best supporting actress.

During her time at Yale University, she acted in another five movies, juggling them with her studies, including a thesis on African-American literature. Henry Louis Gates Jr., then teaching there, was one of her advisers. She baby-sat for his two young children, and he recalled arranging an interview for her with Toni Morrison and telling the novelist only that his student Alicia Foster — that’s Jodie’s real name — was en route.

“When she walked in, I think Toni almost had a heart attack,” Gates, now at Harvard, told me.

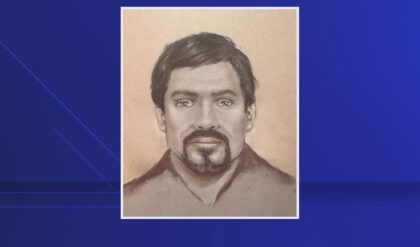

He and Foster remain friends, and he said that he still marvels at the poise that “allowed her to get through a crisis that probably would have been crushing to most of us.” He was referring to John Hinckley Jr.’s shooting of President Ronald Reagan, which Hinckley, who had stalked Foster, said he did to impress her. She was in her freshman year at Yale.

Not long after she graduated, she considered ditching movies altogether and doing graduate work with Gates. The Accused was about to be released, and she was convinced that the movie and her performance were no good.

Her mother, Evelyn, worried that The Silence of the Lambs would be a mistake and, as Foster remembers it, said to her: “The good part is Hannibal Lecter. Why are you taking the dull part?”

Foster is mindful of the privacy of family members, including her two sons, the oldest of whom will leave for college in the fall, and her wife, the photographer Alexandra Hedison. The couple began their relationship soon after that Golden Globes speech and were wed in early 2014. Foster deflected questions about that.

“I never will talk about marriage and friends,” she said. “There are only so many steps I can take to protect people I love. There’s only so much I can do to keep them safe. It’s kind of a horrible feeling to know that if somebody’s close to you, you put them in danger of being hurt, of being sullied — trivialised — just by virtue of knowing you.”

In recent years, she has directed episodes of Orange Is the New Black and House of Cards, picking up Emmy and Directors Guild of America nominations. But her chance to helm movies came earlier, even though that opportunity still eludes many women.

She was spared such resistance because so many male executives “knew me as the eight-year-old who showed up on time, and they didn’t see it as a risk,” she said. “They looked at me as if I was a daughter. They’d seen me grow up. They knew my professionalism.”

So did the Money Monster producers. “Talk to anyone who has worked with her,” said one of them, Lara Alameddine. “They’ll tell you the same thing. She is the most prepared person. She’s the first one there and the last one to leave.”

Foster’s current emphasis on directing over acting partly recognises that at 53, she won’t find as many great roles as she once did. But it also reflects her ceaseless process of self-examination and self-discovery.

“Everybody in my life said to me: When you stop acting, you’re going to be lost,” she said, meaning that directors don’t quite have the visibility and currency of actual movie stars. “What are you going to do when people don’t take your phone call or when you can’t get a reservation in a restaurant?”

I looked for some sign that she was being falsely modest or pulling my leg. Amazingly, she wasn’t.

“Maybe I’ll lose my identity,” she said. “But I guess I need to find out, and I’m willing to take that chance.” — The New York Times