Britney Spears has known the highs and lows of how the US treats its celebrities, traveling from Mickey Mouse club child actor to teen pop icon, to global superstar – and then more than a decade under legal conservatorship after a mental health crisis before winning freedom, for the first time perhaps, to be herself.

But now there are fears of a new chapter in Spears’s saga, or the return to an old unhappy one, after she reportedly had a late-night fight with her boyfriend at the Chateau Marmont in Los Angeles resulting in paramedics being called and pictures of a barefoot pop princess, mostly naked save for a pillow and a blanket, appeared in the tabloids.

Spears, 42, later said she’d injured her foot taking a leap outside her room, and had left the famous hotel with her own security team. TMZ, the tabloid news website, cited sources who feared that she had a “mental breakdown” at the hotel.

Spears later declared “the news is fake” on Instagram and the paramedics’ arrival, triggered by a call from her mother, Jamie Lynne, “caused this huge scene, which was so unnecessary” when all she needed was an ice-pack.

“I’m moving to Boston !!! Peace,” Spears wrote.

Few entertainers have been as compelling and conflicting as the Mississippi-born, Louisiana-bred Spears since her breakout hit … Baby One More Time in 1998 that foretold the coming of a whole generation of Disney child stars that would take over pop music up to the present, now with rising superstar Olivia Rodrigo.

Her career has a litany of memorable milestones, aside from her record of chart-topping hits. There was the onstage kiss with Madonna, who turned out to be one of Spears’s champions; the romance with fellow Mickey Mouse Club star Justin Timberlake; the marriage to back-up dancer Kevin Federline; shaving her head to throw off the paparazzi.

No star, perhaps, has played across the lines of childhood and womanhood more effectively. Or exhibited both the highs and lows of fame so intensely.

Spears has had a historically turbulent time, reminiscent at its bleakest of Frances Farmer, the actress who was subjected to sensationalized accounts of her life, including, as Spears has, involuntary commitment to psychiatric hospitals, and placed under a conservatorship.

And like Farmer, whose mental illness and substance abuse dramatically altered the course of her studio-assigned career, Spears has spent years trying to correct the narrative.

Along the way, she became a queer icon, as Farmer, Judy Garland or Madonna had been before. “We know what it’s like to have our identities cast aside. To feel like we aren’t being heard. To have outside forces pressure us into conforming,” wrote Christopher Rose in Them last year.

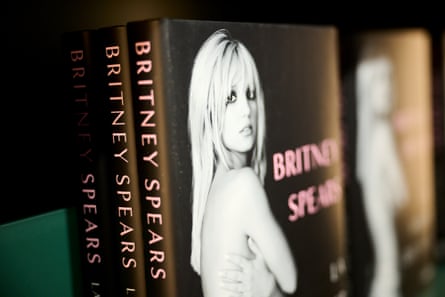

Last year, Spears published The Woman in Me, a stand-out autobiography in which she wrote freely about trying to cope with the pressures of being one of the most famous women in the world, and her struggle to get out of a 13-year court ordered conservatorship that had given control of almost every aspect of her life to her father and lawyers, including access to her two children.

In a review, the New York Times said that Spears had “never stopped telling us who she was – in loopy hand-held videos on Instagram and, naturally, in her vast catalog of songs, with their lyrics about loneliness and emancipation, desire and defiance”.

In a successful 2021 bid to end her conservatorship she told a Los Angeles court: “I’ve been in shock. I am traumatized. I just want my life back.” She also said that when she posted she was OK in Instagram posts, “I was in denial.”

But her posts have recently taken a curious turn. In September, she was seen dancing and wielding kitchen knives, triggering a police welfare check, and later doing handstands in the Las Vegas hotel room she said she’d been living in for four years. On Thursday, she posted another, again dancing, in her room with a wild look in her eye.

Fans have long claimed an innate, subconscious connection with the singer, often via social media, and she with them. They just seemed to “know”, adding “If you stood up for me when I couldn’t stand up for myself, from the bottom of my heart, thank you,” she wrote in the memoir.

“I don’t think people knew how much the #FreeBritney movement meant to me,” she wrote, adding the movement “saved her life”.

Last week, those same fan accounts were stirring anew, prompting a resurgence of an online FreeBritney movement that she credited with helping to end her conservatorship. They see the Chateau Marmont incident as part of an effort to place her back under that control.

Dueling narratives emerged. Some said conservatorship also exposed her to the same forces that may have triggered it in the first place. Others that patriarchal forces, typically expressed through the media, were trying to reassert control of a free bird.

In her autobiography, Spears wrote that while she may not have been “right to spiral”, she was expressing a fundamental right to “test boundaries, to find out who you are, to find out how you want to live”.

But, she continued, “other people – and by other people, I mean men – were afforded that freedom. Male rockers were rolling in late to award shows and we thought it made them cooler. Male pop stars were sleeping with lots of women and that was awesome.”

In contrast to her, she wrote, “no one had tried to take away their control of their body and money”.

Even when her husband cheated on her and acted sexy, she wrote, it was seen as “cute”. When she wore a sparkly bodysuit, TV interviewer Diane Sawyer had made her cry. MTV had made her listen to criticism of her costumes. A governor’s wife said she wanted to shoot her. That criticism, and the control she was placed under, turned her into a robot. “But not just a robot – a sort of child-robot.”

According to Brooke Foucault Welles, professor of communication studies at Northeastern University and author of You want a piece of me: Britney Spears as a case study on the prominence of hegemonic tales and subversive stories in online media, Spears’s battles are part of a larger issue of stories that emerge online, are picked up in the tabloids, but then fall back under the control of a conservatively aligned media.

“What online activism is really good for is questioning mainstream assumptions,” Welles says, “because different kinds of people have the power to introduce different kinds of narratives.

“Early in her career, her manager and parents had control of her narrative. She tried to reclaim power and that power struggle became the focus of her public breakdowns. Social media allowed her to directly reintroduce her voice and perspective, and the fans picked that up as cries for help.”

Britney Spears, then, was never just a pop star but a prism for a larger debate about control.

“There is a collective understanding of what it is to be an independent agent in the world, but that understanding shifts. It is probably different for Britney than it is for you or me, for parents or her publicist. Which one is the truth? I suppose we have to collectively agree on which story we find most compelling,” Welles said.