Jodie Foster has been in the entertainment industry for 50 of her 53 years, going from a Coppertone commercial at age 3 to series television and then to film. She was 14 years old when she was first nominated for an Oscar — for playing a prostitute in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver — and 26 when she won Best Actress for the first time, for the 1988 movie The Accused. She won again soon after for playing Clarice Starling — the character who created an entirely new archetype for a female hero — in 1991’s The Silence of the Lambs.

Given Foster’s background, it is not surprising that she wanted to direct movies from a young age. In a recent interview in Beverly Hills, she called her childhood self “a power-hungry 7-year-old” who had learned early that directing was the way to get to realize “the full vision of the film, and having every part of you expressed.” She was not only in movies, but she was also a film buff. “My mom took me to all these European films,” Foster said. “Lina Wertmüller: That was the first time I had ever seen there was a woman director, and I loved those movies, and I would see them over and over and over again.”

And so Foster started paying attention, she said, “and saying, ‘Why did he do that? Why did he choose this?'”

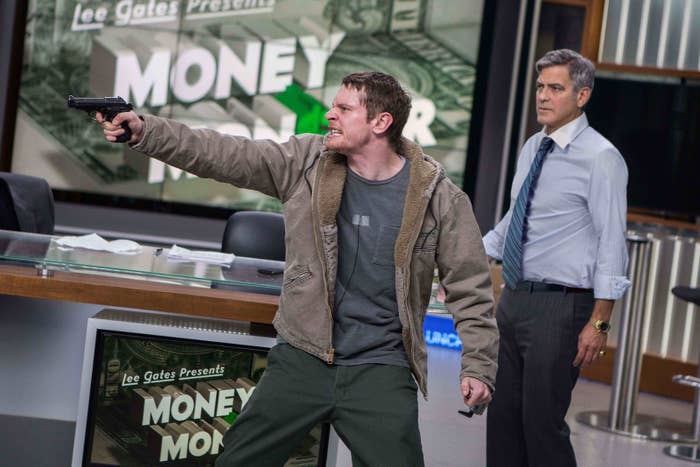

TriStar Pictures

Jack O’Connell as Kyle, with George Clooney as Lee.

The fourth movie that Foster has directed, Money Monster, a hostage thriller reminiscent of ’70s films such as Dog Day Afternoon, will be released on May 13. It co-stars George Clooney as Lee Gates, a cynical finance channel shill, who touts stocks without considering the consequences; Julia Roberts as Patty Fenn, the producer who has grown out of working with him; and Jack O’Connell as Kyle, the angry, duped regular guy who blew his only cash on one of Lee’s tips, and seizes control of the station, with a bomb and a gun, on live television.

Foster sat down with BuzzFeed News to discuss her directing career so far. She was open about how her films have reflected her life, and quick to laugh. She claimed she still enjoys being interviewed, even after all this time.

“I like talking about the movies,” she said. “Who else am I going to talk to about them?”

Little Man Tate (1991)

Orion Pictures Corp/Courtesy Everett Collection

Adam Hann-Byrd, Jodie Foster.

Little Man Tate tells the story of a 7-year-old prodigy named Fred Tate (Adam Hann-Byrd) living in semi-squalor in Cincinnati with his waitress mother, Dede (Foster). Foster had been sent the script, written by Scott Frank, as an actor, but it piqued her interest as a possible first directing project.

“They laughed about that,” she said, without elaborating on who “they” were. She persisted, and found a way to get the movie financed with her directing and co-starring. Foster was 27 at the time, and credits her age with having the “confidence, or maybe the bravado,” not to question whether it was wise to direct both herself and a child who had never acted before. (Hann-Byrd had been discovered in a regular school, not through an agency.) “The good news about being 27 years old is you’re pretty unconscious, and you don’t think about how hard it is what you’re undertaking,” she said.

Orion Pictures Corp/Courtesy Everett Collection

Foster

Foster certainly had her own abundant experiences with directors as a child to guide her — especially on what not to do. “There were lots of directors that worked with me that annoyed me, so I tried to avoid those techniques,” she said. Later, she added: “There’s nothing that I love more than a director who knows what they want. But I especially didn’t want to be manipulated or bullied. And bad things happen to me when I’m bullied or manipulated. It’s the one area where I really rebel, and my way of rebellion is I just get cold. I get cold and totally unemotional and I will not act.”

Fred’s story was particularly important to Foster. Though Dede, a single parent, is devoted to him, Fred is not thriving in public school, nor does he have any friends (his greatest desire). When a school for gifted children discovers Fred — who excels both at math and in the arts — Dede becomes competitive with Jane (Dianne Wiest), the condescending, socially inept head of the school. Their dynamic hurts Fred, but by the movie’s end, Dede and Jane find a balance that serves both his mind and heart. It’s a warm, sweet, intimate film that Roger Ebert described as “the kind of movie you enjoy watching; it’s about interesting people finding out about themselves.”

Foster saw her own past dilemmas in the arc of Little Man Tate. “It’s a personal movie even though it was written by somebody else; I feel like it’s an auteur film,” she said.

“I really saw myself as somebody who was pulled in two different directions,” Foster continued, describing her bifurcated childhood. “I had this weird emotional intelligence about people, and why they do what they do and trying to figure out how to help take care of people. But I also really felt great joy, and lived in the world of my intellect.”

Though Little Man Tate shows the audience some of Fred’s talents, they’re not the focus of the film — his awkward, poignant attempts to fit into the world are. It was a deliberate choice of Foster’s. “Some of the criticism of the movie was, like, Wait a minute, this is a movie about a child genius: Why don’t we talk about all the amazing things he does? Why don’t we talk about his joy with math?” she said. “I was, like, ‘Well, I was a prodigy, and I don’t want to talk about that. I want to talk about how lonely I was.’”

Orion Pictures Corp/Courtesy Everett Collection

Dianne Wiest, Hann-Byrd, Foster.

But Foster is also critical of her directing work. With Wiest, she said, she tried to “control her performance too much.” Jane, a brilliant snob who begins to discover her maternal side with Fred, was a different sort of role for Wiest, who had played spaced-out, warm-hearted characters in Footloose, Hannah and Her Sisters, and Parenthood. “She has this beautiful, kind of bubbling way about her where she kind of discovers the lines in the moment,” Foster said of Wiest — and that couldn’t be the case with Jane. “I forced Dianne to be so meticulous and so rigid, and I know it wasn’t her instinct,” said Foster. “And I still feel bad about it. But I think it’s a great performance.” Nevertheless, she said, “I always apologize every time I see her.”

Though Foster said the movie was “naïve,” “very plodding and black and white,” and that she made her points “in a big way,” she’s still proud of her directorial debut.

“I think more than anything else, it just has a lot of heart,” Foster said. “And mostly because it came from a really personal place: the theme of being alone, and knowing that you’re different, and knowing that you’re never going to belong, and you’re never going to be like everybody else. I think that was a theme in my life as a young person. It is as I grew up. And I was just starting to understand that then.”

Home for the Holidays (1995)

Paramount/Courtesy Everett Collection

Holly Hunter, Robert Downey Jr.

After directing Little Man Tate — as well as winning that second Best Actress Oscar for The Silence of the Lambs — Foster formed a production company, Egg, and entered into a deal with PolyGram Filmed Entertainment, a studio that eventually merged with Universal. “Failed moguldom!” she said with a loud laugh. “I was following a path, and — I can’t say I think it was a mistake? But it was a lot of energy output, and I think the energy would have been better spent in other places. When you’re young, you try things.”

She added: “I think people thought I wanted to make big, mainstream movies, and the truth is I didn’t. I just wanted to make movies that were relevant to me.”

Nell in 1994 was the first film that Foster and Egg produced, and it was set to be released just as she began to prepare to direct her next feature, Home for the Holidays, a drama/comedy about one loud, messy family’s Thanksgiving weekend. Foster developed and starred in Nell, in addition to producing. It was an immersive performance, with Foster playing the title role of a young woman who had lived in isolation with her mother and created her own language before being discovered by doctors. “Nell was tough,” she said. “People did not respond to the movie, they didn’t like the movie. And I was really out there. I really put everything on the line.”

Foster would go on to be nominated for Best Actress again for Nell, but as she absorbed the criticism of the movie, she dove into Home for the Holidays. “It was a good way of curing the ills of an unsuccessful movie,” she said.

Foster had bought Home for the Holidays after another company decided not to make it. It was based on a short story by Chris Radant, and she would be only behind the camera this time: no acting.

Paramount

From left: Steve Guttenberg, Charles Durning, Anne Bancroft, Cynthia Stevenson, Dylan McDermott, and Hunter.

The film stars Holly Hunter as Claudia, an art restorer in Chicago who is fired from her museum job just as she is about to head to her parents’ house for Thanksgiving. Once there, she is infantilized — if lovingly — by her eccentric parents, played by Anne Bancroft and Charles Durning. It was a large ensemble: The cast also included Robert Downey Jr. as Tommy, Claudia’s charismatic, mercurial, gay brother; Dylan McDermott as Tommy’s friend and Claudia’s love interest; Cynthia Stevenson as Joanne, Claudia and Tommy’s sourpuss sister; Claire Danes as Claudia’s sophisticated teenage daughter; and various other family members of all embarrassing stripes.

With this crowd, the script ended up changing significantly during the rehearsal period before the movie began shooting, and Foster worked closely with screenwriter W.D. Richter (The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension). “So much of the overlapping dialogue and their dynamic with each other was really important, mostly for shaping the screenplay,” Foster said. At this late stage, as the actors, Richter, and Foster workshopped the script, the focus of the movie became the warm relationship between Claudia and Tommy. Hunter, Foster said, loved to “react to other people.” And so, “it was about engineering things for Holly to react to — she was the person reacting to all this craziness around her.”

Paramount

Downey

Downey was in his wild-man days then, and was steps away from going into rehab (one of many times in the years to come). Yet the open process during Home for the Holidays served his talents well. “He really fleshed out that character in a way that I wouldn’t have been able to,” Foster said. In her and Downey’s hands, Tommy ended up being one of the most fully developed, realistic LGBT characters popular culture had yet seen: He is the object of his parents’ silent homophobia, and of his sister Joanne’s more vicious strain, but he has found joy in his home life with his husband — Home for the Holidays features one of the first same-sex weddings in film. (Foster came out of her own glass closet in 2013 at the Golden Globe Awards.)

“He’s a verbal guy who can live performatively on the outside of his body,” Foster said of Downey and the creation of Tommy. “But there’s also such pain in that character, knowing that he’ll never really be able to talk to his father, and that his mother is busy ignoring who he really is. The only person he connects to is his sister, mostly because she’s an outsider as well. And they will forever be eating Thanksgiving dinner alone in the kitchen without everybody else there.”

The Beaver (2011)

Summit Entertainment

Mel Gibson

Foster would not direct again for years, but she certainly tried: Flora Plum, a drama set in a 1930s circus, was first announced in 1999 and was to film the next year, starring Danes and Russell Crowe. But it was scrapped after Crowe injured himself right before shooting began, and Foster’s subsequent efforts to get the movie going again did not work. As recently as 2008, she thought she still yearned to do it — until she realized that she actually didn’t.

“That was many years of my life,” she said. “And that was just a testament to a bad part of my personality too — that I can’t let things go, and I just keep banging myself against a wall over and over and over again! To the point where, 10 years down the line, I get that movie financed — I finally get that movie financed, again, for the third time — and I’m about to get to the point where they’re dropping the money into the escrow. And I go, like, Wait a minute. I feel like I already made this movie. I feel like I grew out of this movie now!”

Between Home for the Holidays and The Beaver, Foster also had two sons, who are now in their teens. “I was really present for their lives,” she said. “And maybe because I’m so focused — overly, hyperfocused on one thing — I think I was scared of leaving them, and focusing on that other thing.” She continued: “And I can’t regret that. I don’t regret that I was there every single day for every single thing that they did. And acting allowed me to do that. I couldn’t do that being a director.”

During the 2000s, she was in such movies as David Fincher’s Panic Room (2002), Spike Lee’s Inside Man (2006), and more — but the acting lessened too. “I burned out a little,” Foster said. “I’m not going to be one of those actors who’s like, ‘Oh, yeah, I’m only going to give you five days, and we can’t work past 5, and my kid’s going to be in my trailer. I only shoot in L.A.’ That’s not going to be me! I’m going to commit 100%. Otherwise, I don’t know how to be good. It means that I only did one movie every three years.”

Despite knowing why she made the choices she did, and what she was doing instead, Foster said she feels bad about how rarely she has directed. “That’s a big failure in my life, you know?” she said. “I can’t believe that I’ve directed so little, and I’ve been in the business for so long, and I did my first movie when I was 27.”

Summit Entertainment

Riley Thomas Stewart and Gibson.

The Beaver by Kyle Killen was on the 2008 Black List, Franklin Leonard’s annual survey of the most popular unproduced screenplays (as picked by Hollywood executives). It was the story of a depressed CEO named Walter Black whose breakdown is so acute that he is revived only when he begins speaking through a beaver puppet he wears on his hand. Before Foster signed on to direct, it was geared to be more of a comedy, and Steve Carell was set to star in it.

Foster did not see The Beaver that way. “That was a very strong choice that I made that I know was not for everybody,” she said. “The movie that I loved was the drama about a man who’s so broken and hates himself so much that he has to put a puppet on his hand in order to figure out how to survive. I wanted the darkness of it, and I wanted the emptiness of it to reflect who he was. I wanted it to be a film about mental illness.”

Foster wanted Mel Gibson — her good friend, with whom she had starred in 1994’s Maverick — to play Walter. Gibson’s anti-Semitic outburst during a 2006 DUI arrest had put him on the fringes of the entertainment industry; and even before that, he had not starred in a movie since 2002’s Signs. But he was Foster’s first choice. “He knows how to do comedy, and he has a light touch — and he’s lovable. But he would really understand this movie from its darkest place. And that’s really what I wanted to push him to do,” she said.

Despite not liking acting in the films she directs, she cast herself as Walter’s estranged wife, Meredith. “I wanted to know that the person playing opposite him was going to honor the performance that he was giving and was going to be believable, and had the strength to stand opposite Mel Gibson,” she said. Anton Yelchin played Porter, their high school–age son who despises Walter, and Riley Thomas Stewart was cast as Henry, their younger kid, who loves Walter and yearns for his attention.

Summit Entertainment

Jennifer Lawrence

Foster had difficulty finding someone to play Norah, Porter’s love interest, until she came across Jennifer Lawrence’s casting tape. It was 2009, and Lawrence would break out in Winter’s Bone the next year, but at that point, she had mostly been on television. Foster called her audition “extraordinary,” and it in fact made her realize that the character had been written wrong. On paper, Norah was the class valedictorian and a cheerleader and “she’s got all this banter,” Foster said. “And you’re, like, Who is that? I mean, who in the world is that! That’s just some male fantasy. And it was weird having this one actress play all these perfect things — it was annoying, actually.” Foster went back to the script to write it for Lawrence. “I made her less verbal,” she said. “She’s best when she’s unconscious, when she’s not an intellectual. So I took all of the Woody Allen out of the character.”

Toward the end of the movie, Walter feels so trapped by the beaver — even though it has brought him back to himself and his family, and has made him a success in business again — that he cuts his arm off, and barely survives. “I wanted it to be moving, and I wanted to get to the end of the movie and understand why he had to cut his arm off,” she said. The tone of the movie, deeply sad, yet also funny and hopeful, was difficult to strike. How did she do it on a daily basis? “I don’t know. Imperfectly. And I’m sure lots of people would say I did a terrible job,” Foster said.

The Beaver might have been a tough sell for audiences under any circumstances, but it turned out not to matter. As Foster was doing reshoots in 2010 to prepare for its fall release where it would have been positioned as an Oscar movie, Gibson told her that tapes of him screaming at his ex-girlfriend Oksana Grigorieva were going to come out soon. In the tapes, published by RadarOnline, Gibson admitted to hitting Grigorieva while she held their child, threatened her, and used vile epithets throughout. The Beaver no longer stood a chance with mainstream audiences.

Summit Entertainment/Courtesy Everett Collection

Foster and Gibson.

Foster, who has remained friends with Gibson and strenuously defended him over the years, said her first reaction to the tapes was that Summit, the studio behind The Beaver, “would just shelve the movie and it wouldn’t come out.” Instead, the film was delayed: It premiered at the SXSW Film Festival in March 2011, and then opened in limited release two months later. According to Box Office Mojo, it grossed less than $1 million domestically, with an additional $5.4 million worldwide, on a budget of $21 million.

Yet in what might be the most unexpected bright side of all time, Foster said, “Once the studio knew that they had a limited release and they were never going to be able to release the movie well anyway, they left me completely alone. Yeah, whatever score you want!” Gibson’s meltdown had destroyed what would have been an attempt at a comeback for him, as well as a probable push for a Best Actor nomination for his layered, tragic performance. But, Foster said, “I actually got to make the movie I wanted to make. And that is reward in itself. I won the big prize. And I got such an extraordinary performance out of him. And I have a DVD.”

The Beaver was the final chapter in what Foster thinks of as “sort of a trilogy” — her autobiographical first three movies. “Early years as a prodigy, middle years of being torn with your family and trying to figure out who you are, and then that middle-age crisis,” she said. She has spoken in the past about depression being a part of her life, and yes, The Beaver reflected that. “A spiritual crisis, and the creativity that comes from a spiritual crisis. That was such a big part of my life, and I had a lot to say about that,” Foster said. “As an allegory, that film was totally me.”

“And he is reborn at the end of the film,” she continued. “He has to become a new person that is a small, frail, not very grand person that’s missing an arm in order to reconnect and remember who he was. And remember his relationships.”

Orange Is the New Black (2013 and 2014) and House of Cards (2014)

Netflix

Laverne Cox on Orange Is the New Black.

In recent years, Foster has directed three episodes of television for Netflix — and she really likes it. “It’s just a way of keeping your hand in,” she said. “I like serving a creator, and going, ‘You do a thriller? Great, I can do a thriller.’ Because I’ve done all kinds of movies, so it’s easy for me to go back and forth and to honor their system.”

Having worked with Fincher on Panic Room, for instance, Foster felt confident that she knew what he would want visually for a Season 2 episode of House of Cards. She directed “Chapter 22,” in which the Underwoods’ ascent is threatened by Claire’s affair being exposed; it was also the episode in which Francis had to cut ties with Freddy, his favorite barbecue artist. “When you work for David Fincher, you know it’s all prime lenses,” she said. “And there will be no red! You know what the template is, and I love serving that template.”

Both of the Orange Is the New Black episodes she directed were pivotal for the series. The second one, “Thirsty Bird,” was the Season 2 premiere in which Piper (Taylor Schilling), having beaten the shit out of Pennsatucky (Taryn Manning) in the first season finale, finds herself on a plane to what is eventually revealed to be a Chicago prison to testify in a trial. Viewers are meant to be as confused as Piper for awhile, and it’s disorienting: The only familiar faces in the episode are Schilling’s and Laura Prepon’s as Alex Vause. To do something with almost an entirely new cast, and, “real sets, hardly any built sets at all,” was “like doing my own pilot, which was nice,” Foster said.

For Foster’s first Orange Is the New Black episode — “Lesbian Request Denied,” the third episode of Season 1 — she was nominated for both a Directors Guild of America Award and an Emmy. “Lesbian Request Denied” made clear early in Orange Is the New Black’s life that, because of its portrayal of the varied, tragicomic world of American women in prison, it would be like nothing that has ever been on television before. The episode featured the backstory of Sophia (Laverne Cox), the transgender inmate who went from firefighter to convict as she paid for her transition through fraud. It was sad, moving, and surprising — and the episode’s humor came in the form of Suzanne “Crazy Eyes” Warren’s (Uzo Aduba) relentless obsession with Piper. “Chocolate and vanilla swirl, swirl,” Suzanne sings to Piper, in a much-quoted and GIF’d line. (“I cast Crazy Eyes. I cast Uzo!” said Foster.)

“With comedy-drama, it takes awhile to figure out what the tone of it is,” Foster said of Orange Is the New Black. “That’s what I do for a living, I do comedy-dramas. So I feel like they were finding their way a little bit, and that episode maybe kick-started them in a certain direction.”

And did Foster think it was funny that she — of all people — was directing an episode called “Lesbian Request Denied”?

“It was fantastic,” Foster said. “I laughed. It was almost as good as making a movie called The Beaver.”

Money Monster (2016)

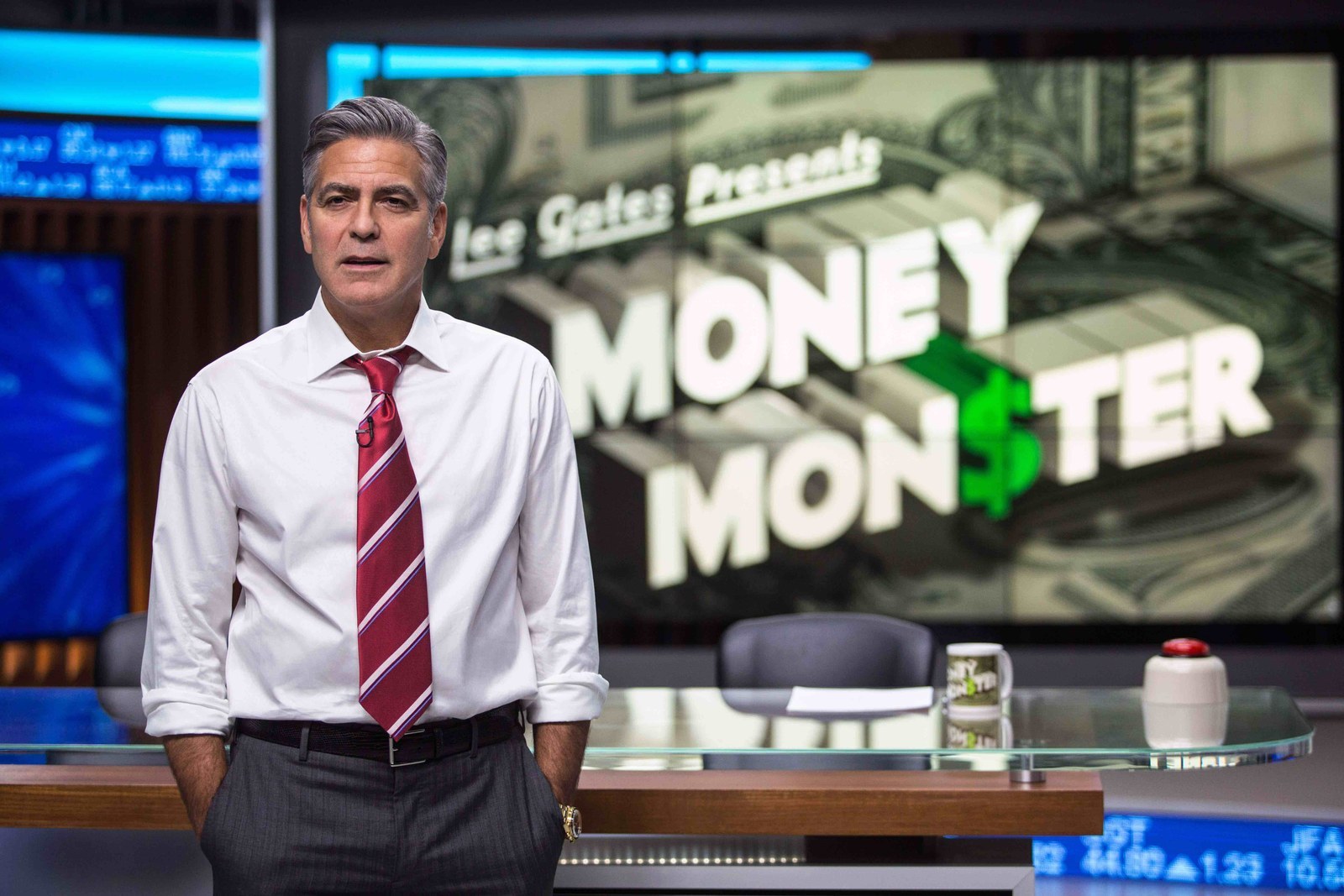

TriStar Pictures

Clooney

Money Monster is different from anything Foster has previously directed. It’s a large-scale thriller with an explicitly political spine — with major movie stars in the lead roles. She was attached to the project during the script stage, and liked that it was both a “real thinking man’s movie” and a “general public movie.” Kyle has strapped a bomb on Lee, and has a gun pointed at him, but — of course — as the movie goes on, the audience sees that he is not only right about Lee’s character, but about the criminality of modern finance. And Lee, in turn, has a chance to be redeemed.

Its commentary on the terrifying realities of the financial world resonated with Foster. “It’s so many layers and so much modern social relevance about what’s going on today with entertainment and politics and finances and technology and how all those things are put together in this weird mishmash,” she said.

“That being said, for me it’s really about these small character pieces, and the theater of these two men, and the woman that’s producing their survival,” she continued. “And their dynamic and their relationship and how they change — these two guys looking at failure. They start off thinking they’re the opposites, and yet they have so much in common. Because they hate themselves.” (When it was pointed out to Foster that she had similarly extolled self-hatred in the Walter character in The Beaver, she said with a laugh, “I do like that as a theme!”)

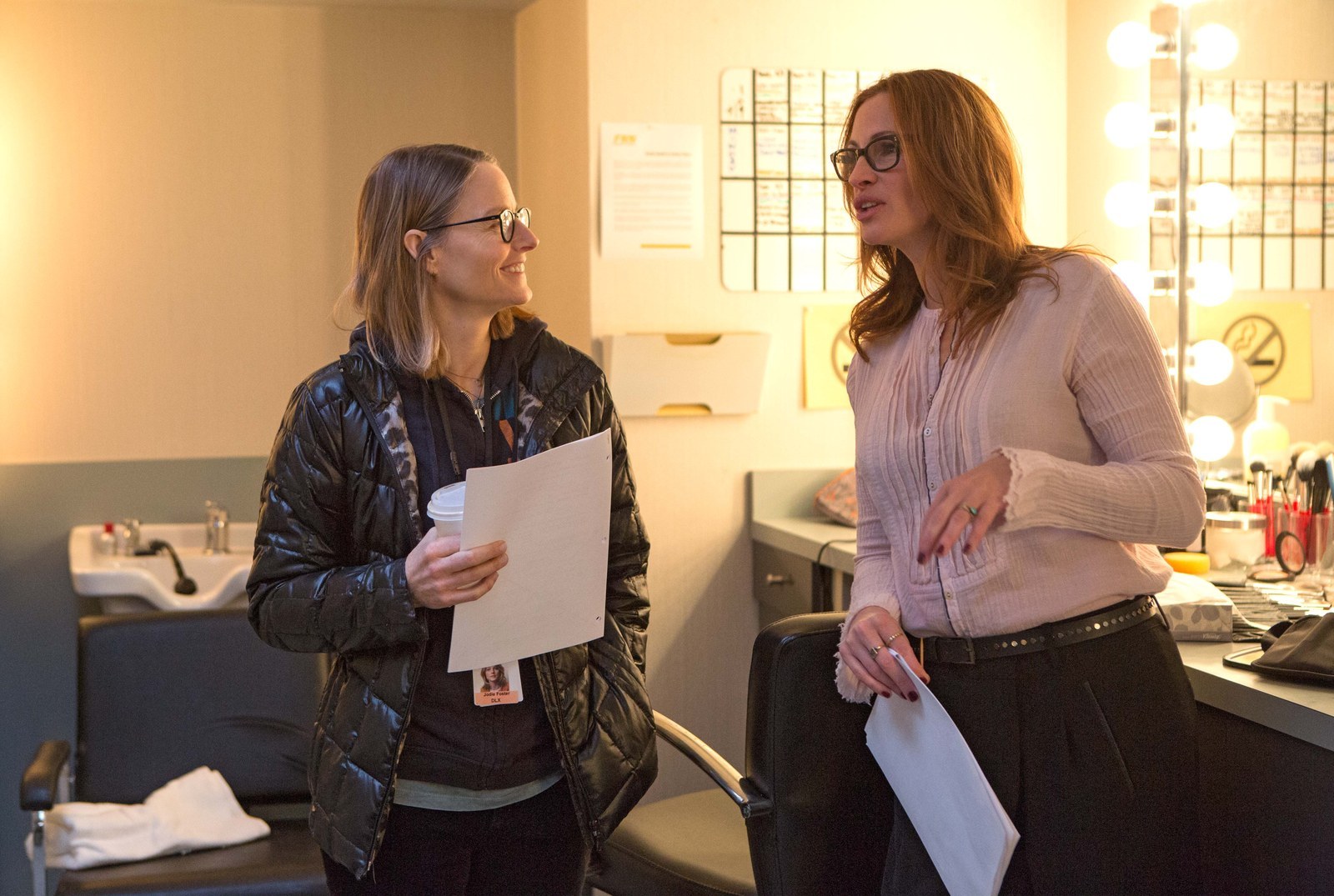

TriStar Pictures

Roberts

Filming the movie presented a number of technical challenges. It unfolds in slightly fudged real-time, and Patty is watching Lee and Kyle on monitors in the control room from which she produces the show. Foster said she realized as she prepared to shoot the movie that meant that all of the scenes on the set needed to be shot first — and in sequence — in order for Patty to talk to Lee through an earpiece, and to react to what is happening between him and Kyle. It also meant filming what’s on the monitors themselves during Roberts’ scenes. “And they all have to be correct; it’s not like we can change them,” Foster said.

Another logistical difficulty was that Roberts had only eight days available to film, so Foster had to use the actor’s time judiciously. Luckily, Roberts came prepared. “I don’t know whether she’s pretending that it’s all effortless, and it doesn’t take any energy at all and it’s all just fine,” Foster said. “She knows everything about television broadcasting, she’s got every single line written down, she knows everyone else’s lines, she knows which buttons she’s pushing at what time. She’s got the whole thing worked out in the earpiece. She’s amazing. And then she’s, you know, knitting and talking shit.”

Foster was also grateful to be able to rely on Roberts’ and Clooney’s real-life camaraderie to make the Patty–Lee friendship believable — it does, after all, provide Money Monster‘s emotional core. “She’s sort of his Jiminy Cricket,” Foster said. “This virtual intimacy that they have is weirdly closer than if they were standing in the same room together.”

“There’s that chemistry they have that I have nothing to do with, that’s just like a god chemistry between the two of them,” Foster continued. “They finish each other’s sentences, and you just know they’re brother and sister. You can’t manufacture that.”

TriStar Pictures

Roberts and Foster.

With its helicopters and police vans and hundreds of extras, Money Monster isn’t the sort of film that is often directed by a woman. And the recent questions and criticisms about the lack of female directors in the mainstream entertainment industry is an issue on Foster’s mind. It’s been a “prickly path,” she said, especially once Hollywood’s output became a global business. “They’re looking to keep their risks as small as possible, because they’ve got a lot of risks on the line,” Foster said of studio executives. “And I guess women are risks. And as that’s gone on, that’s why it’s a less diverse canvas than it’s ever been in the mainstream movie industry.” Even when studios have been run by women, “it didn’t change anything — the lists were still the same when it came down to it,” she said.

Foster does feel that things are changing. But, she said, “It’s a complicated issue. The discussion is a little simple. And we’re not going to get there with quotas.”

“You can’t legislate how art is done,” she added. “And you also have to embrace the fact that men and women are different, that we lead differently, that we are interested in different things.”

For someone who literally grew up in Hollywood, it is an uncomfortable topic for Foster, who prizes loyalty so much. She is frank about the dilemma she feels. “It’s hard for me,” she said, “because these guys, these old guys — those are the guys that gave me my opportunities, that believed in me, and that brought me up like their daughter. I was always surrounded by men. And I was surrounded by cigar-chomping sexist men, too. Who loved me! Who took care of me, and believed in me. So it’s hard. It’s not my nature to be—” She paused. “To kick anyone in the face.”

Of course she wants things to change, though, even if the process is slow. “You can’t go into an elevator without encountering sexism; it’s part of being a woman,” Foster said. “And I don’t need to eradicate it in a way. I just need to be able to make small steps so we can change the culture little by little.”

Of course, she already has. She played a kickass tomboy in Freaky Friday; a rape survivor who wouldn’t give up in The Accused; an FBI trainee who faced down a serial killer in The Silence of the Lambs; and an intrepid mother who would do anything to save her daughter in Panic Room. If those steps toward changing audiences’ perception of women once happened mostly in front of the camera, Foster is now focused on making a lasting impact as a director.

“I feel like my whole life has worked up to this. Yeah, I’m a young director. I’ve only done four movies, and I have a lot to learn, and I’m excited about that,” she said. “I’ll always act. But I want it to be special. I’d like to try new things as an actor, and in order to do that, I can’t burn out on doing the old things over and over.”