The crime drama is nearly as old as television itself, with its first success, “Dragnet,” making the jump from radio to the tube in the 1940s, and the genre has thrived ever since. However, while some modern shows have successfully used the format to talk about bigger things, it’s a harder genre to love today.

Though enjoyed worldwide, cop and crime shows in the U.S. haven’t always kept up with the culture. While most of the best examples we have can look, unflinchingly, at some of the too-optimistic portrayals of the police and discuss them, some still retain the Western-style simplistic polarity of bad guys versus good. Crime, and the societal breakage that helps it happen, is a tough topic. But it’s not one we ever tire of. And throughout our media history, it’s more than something our Dads love to snooze to. The crime drama will always be part of our cultural heritage. Let’s take a look some of at the best examples of how it earned its place.

Dragnet

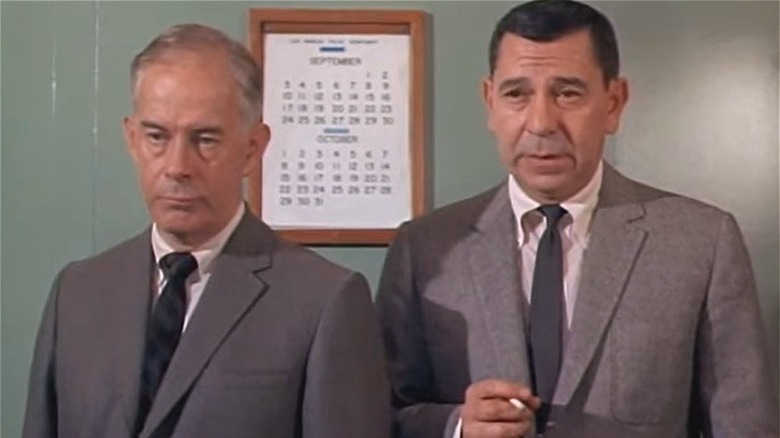

“Dragnet” originated on radio in 1951; created, produced, and sometimes even written by Detective Joe Friday himself, Jack Webb. Possibly the avatar of crime drama, Webb inhabited Friday’s stoic form for hundreds of episodes across decades. The final total of “Dragnet” episodes is over 750, including its radio era, and save for 74 episodes across two revival series that aired after the creator’s death, Jack Webb was Joe Friday for all of them.

“Dragnet” is the Ur-Procedural, the show that formed how we still think about cop shows today. Friday and his partner, Frank Smith in the original and Bill Gannon in the ’60s revival, showed the gritty, real work of solving crimes. With its fast-paced episodes often pulled from real Los Angeles crime files, competent cop Friday highlighted everything from homicide to street scams. Enduring enough to have a loving parody movie in 1987, starring Tom Hanks and Dan Akyroyd, “Dragnet” still echoes throughout pop culture. Its tinny, four-note theme is buried in your head somewhere. You may not know how it got there. But it’s going to survive the heat death of the universe.

Alfred Hitchcock Presents

Less about the police than the psychology behind mystery itself, “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” was what you binged instead of “The Twilight Zone” if you wanted to watch people really go through it. Similar to its compatriot, this anthology series was hosted by the man himself. Hitchcock was well-established as a god-tier director when his series first aired in 1955. Of over 260 episodes, Hitch directed 17. In 1962, mystery buffs couldn’t get enough and the series was retooled into “The Alfred Hitchcock Hour” for another 93 episodes.

Each episode saw the director’s hand-drawn caricature enter to the infamous tune of “Funeral March for a Marionette,” a jangly piano piece that evokes oddball mystery. One of the best episodes, in my opinion, is “The Perfect Crime,” directed by Hitchcock and starring Vincent Price. It’s a tense ride as criminologist Price cobbles together said perfect crime, and it’s a talkative one. For more gleeful crime fans, there’s “Lamb to the Slaughter,” also directed by Hitchcock and based on a — yes! — Roald Dahl story. Not to spoil the surprise, but “Hannibal” fans, this classic’s for you.

The Fugitive

Dr. Richard Kimble’s been on the run for a long time, first hitting the streets in 1963. The 1993 Harrison Ford action thrill ride is an excellent distillation of the classic series’ big moments, which were originally doled out over the course of 120 episodes. The one-armed man, who never has a confirmed identity, is seen rarely until the two-part finale where Kimble finally catches up with his wife’s true killer.

The rest of the series is full of close-calls of the week, where the capable but disgraced Dr. Kimble helps people in need wherever he goes. It’s his empathy and need to help that makes him so plainly innocent, and makes his lawful nemesis, Lieutenant Gerard, feel robotically unsympathetic. The law is the law, believes Gerard. Proclaimed innocence and the facts of Kimble’s rampant kindness aren’t relevant. Only the finale makes Gerard human.

This classic cat and mouse series continues to inspire. Naoki Urasawa’s stellar manga “Monster,” with its equally honorable Dr. Kenzo Tenma, may be the best homage Richard Kimble could have ever asked for.

Columbo

Peter Falk has the right kind of gravelly voice to sound both charming and scattered. His seminal role as Lieutenant Columbo in, what else, “Columbo,” takes advantage of this. Columbo acts like he’s got too much Peter Sellers in him, an eccentric that bumbles his way through crime scenes for an episode’s given running time. But fans who love this classic detective know it’s all an act.

Well, sort of. Columbo is polite and eccentric. But he’s also smart as hell, and he knows exactly how he’s perceived. His targets are rich scumbags who think they’ve gotten away with their crime. Columbo relies on psychology as he quietly interrogates his prey, wearing their defenses down until he kills them with his signature whopper: “One more thing, sir…” Columbo always gets his man, the right man, and from the get-go. It’s comforting stuff from a time when cops were as blue collar as the rest of us, keeping the elites in line. That theme may not have aged well, but the show does, purely because of Falk’s immortal charm.

Kojak

The culture found bald men sexy well before Sir Patrick Stewart helmed the Enterprise. The sleek-domed Telly Savalas made cops into cool cats back in 1973 as “Kojak,” a former street kid hip to the new world and ready to save the people he grew up with. Savvy and cynical, he retained empathy for witnesses and criminal informants, whatever side of the street they came from. But he didn’t take disrespect, either.

Lieutenant Theo Kojak is the forerunner of plugged-in cops like Sonny Crockett and Bobby Simone, a man who embodied the era he was in. The early ’70s still wrestled with concepts like basic civil rights, and “Kojak” recognized the tension. Kojak was a composite of several cops, including Detective Thomas Cavanagh, who worked the Career Girls Murder, a case so famously fraught with racist police coercion that it formed the basis of Miranda vs. Arizona, or, the reason cops have to read you your rights.

Cagney & Lacey

Cop dramas were a boys club in the ’80s, and frankly, they still are. The first major attempt to attack the status quo came in 1981, as Christine Cagney and Mary Beth Lacey took to the New York streets to show the world that solving crime has no gender. “Cagney & Lacey” fought to become a hit, surviving an early cancellation via a fan-run letter campaign.

The pair do their best to show the breadth of life experiences women can have, with Cagney as a career woman and Lacey as a working mom. The show doesn’t shy away from big issues, with a toady little dude named Newman benefiting more from the old boy’s network than them on the way to a promotion. Discrimination and harassment became the core of “Rules of the Game,” which sees Cagney under the thumb of a controlling police captain. It’s ridiculous that there’s been nothing quite like “Cagney & Lacey” since, though at least great partnerships like Elliot and Stabler have become regular delights.

Hill Street Blues

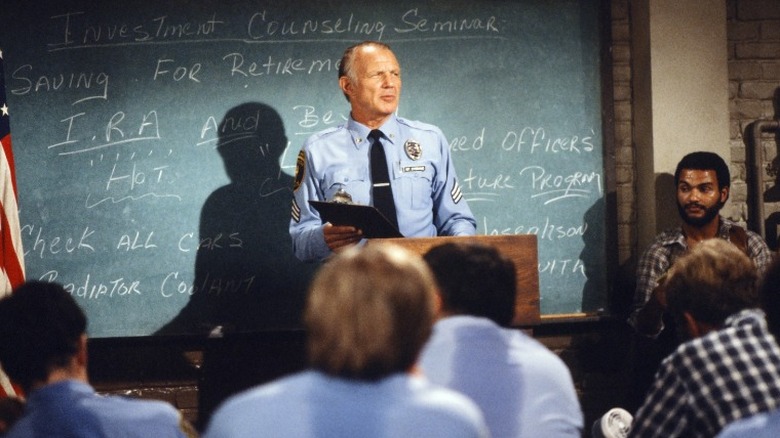

Cops work out of individual precincts, part of squads and thus, part of a weird, sometimes grotesque family unit. Until 1981, that sprawling connection wasn’t ever explored. Enter “Hill Street Blues,” with a cast that effectively numbered into the dozens over its seven season run, and which took its audience as close to the action as possible with documentary-style camera work and a glimpse of how the job became part of a cop’s personal life, too.

“Hill Street Blues” was also the first crime drama to allow storylines to weave in and out across a season, with the fates of its characters always at risk from a bad day on the streets. Edgy for the time and chock full of dated sensibilities, it still helps shape the perception of street police today. But more fun, like its descendant, “Law & Order,” it’s also a terrific show to binge for “Hey, it’s that guy!” moments. Guest stars range from Danny Glover and Tim Robbins to giving first roles to actors like a young Don Cheadle.

Miami Vice

Underneath the hood, however, “Miami Vice” will always be a Michael Mann production, and that keeps it working. With its deliberately Art Deco aesthetic, its caseload somehow still feels fresh and the fashion feels fantastical instead of dated. As part of Miami’s vice squad, the perps our pastel princes are up against are drug lords and scammers. It doesn’t lower the stakes, but it enhances the stylish sensation that everyone is looking to make it big off the back of someone else. Like other enduring shows, part of what works is its tasty synth theme song, a Jan Hammer special beamed in from a universe where the best of the ’80s will never die.

Murder, She Wrote

Cozy mysteries are one of the hottest subgenres to currently exist, with cats, coffeehouses, bakeries, and, occasionally, globetrotting romantic adventures setting the stage for crimes of all kinds. 1984 offers a partial genesis for this popularity, with Angela Lansbury as the star of the 12-season-long classic “Murder, She Wrote.”

Yes, it’s the series from fictional Cabot Cove, the bucolic Maine hamlet that offers a body count so severe that it made headlines in 1992 for outpacing countries with thriving cartels. I don’t believe Jessica Fletcher has ever asked herself the “Batman” question: Would Cabot Cove be so bloody if Fletcher wasn’t there to observe the mayhem? Regardless, it’s still a pleasure to explore the countryside with Jessica, even though later seasons see her as a teaching criminologist in residence in New York City. Really, by then, this unassuming novelist had long since proved she can do as well as she can mentor.

Cadfael

Lost in the trove of better-known ’90s mystery series is a wonderful English import called “Cadfael.” Starring Sir Derek Jacobi as Brother Cadfael, a 12th Century Benedictine monk, it’s a rare treat for fans of the earthier, more human version of the Middle Ages we’ve seen in recent works like “The Green Knight.”

Based on the novels of Ellis Peters, Cadfael is a former crusader and soldier, who saw Jerusalem under the reign of Baldwin I. Weary of doing harm, he turns to herbalism. Though he’s Shrewsbury’s foremost healer, he also becomes the local medical examiner. Local sheriff Hugh Beringar grows to appreciate the aging monk’s guidance, though Cadfael’s amused acceptance of the secular world often puts him at odds with his Benedictine superiors. With only 13 episodes, the often historically accurate “Cadfael” is tempting to binge. But savor it instead; there’s nothing else quite like this gentle monk with a keen understanding of the world around him.

Law & Order

It’s gauche to highlight the name of legendary producer Dick Wolf, and besides “30 Rock” did it better. Yet the Wolf is indeed a legend, honing his writing skills on “Hill Street Blues” before creating the unstoppable juggernaut franchise “Law & Order.” With eight series total – not counting “Law & Order UK,” which is the same formula but with crown prosecutors in silly English wigs – it’s thousands of hours of criminal-hunting fun.

With the original series back for more as of 2022, it’s fascinating to see how the often-realistic process of investigation has changed since first airing in 1990. The detectives are on the streets less than ever, with smartphones and an in-office expert controlling most of the show. The spin-offs rely more on interpersonal drama, with “SVU” fan favorites Elliot and Stabler as one of TV’s biggest comfort couples. There’s really no way to describe how influential and how massive the “Law & Order” franchise is, nor how often classic episodes will stun you with early appearances from Sebastian Stan to Sam Rockwell.

Homicide: Life on the Street

David Simon was a journalist for the Baltimore Sun when he embedded himself with the city’s homicide department for the entire year of 1988. The result of his observations were chronicled in “Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets,” one of the most nakedly truthful books about the world of murder to exist. Its adaptation went to air in 1993, its title softened to “Homicide: Life on the Street.” It retained much of the book’s truthfulness, however, showing the flaws and obsessions of each detective as their caseloads erode their spirits, and sometimes, their humanity.

Yaphet Kotto stars as Lieutenant Al Giardello, based on the real-life shift lieutenant Simon knew as Gary D’Addario. His crew often changed throughout the years, but among them, actors Andre Braugher (“Brooklyn Nine-Nine”) and Richard Belzer (“Law & Order: SVU”) stayed throughout. The crimes also remained, and the specter of Adena Watson, based on a still-unsolved slaying of a little girl named Latonya Wallace, haunted one of its detectives for the entire series run. Though the series stumbles in its final seasons, it remains one of the best crime series you’ve probably never watched.

NYPD Blue

Watercooler television is less of a thing in the modern era of streaming services, though it still exists. But in the ’90s, having a show everyone talked about at lunch the next day was a measure of irreplaceable success. “NYPD Blue” was one of those shows, a barn burner from Steven Bochco (“Hill Street Blues”) and David Milch (“Deadwood”) that highlights its detectives above and beyond the crimes they investigate.

Individual crimes fade into the background in favor of Detective Andy Sipowicz’s effort to become a better person. Played by Dennis Franz, the initially ugly-of-spirit Sipowicz becomes the show’s de facto protagonist, an old guard blue line mess who gradually joins the modern era. Controversy made this series eternal; it frequently pushed broadcast standards with adult nudity and language that was so spicy that it forged a right-wing censorship group in the Parents Television Council. The PTC’s attacks seem to, if anything, have resulted in more bare butts for adults to enjoy.

Nero Wolfe

Rex Stout’s garrulous but insulated Nero Wolfe has undergone a number of adaptations since his debut in 1934. The best version is, easily, A&E’s 2001-2002 20-episode collection of “Nero Wolfe” stories. With the late and deeply lamented Maury Chaykin as Nero and Timothy Hutton as his assistant and extroverted gopher Archie Goodwin, the pair navigate the mysteries that the stymied police delegate to them.

Nero charges the cops extravagant fees — king move, honestly — to supplement his luxurious but close-quarters lifestyle. He’s not agoraphobic, he’s particular. Nero’s brilliance also forces his clients to put up with his ways, and deal with his gopher Archie at crime scenes and at a witness’ side. When guests are permitted inside Wolfe’s imposing brownstone, they are entirely at Wolfe’s intellectual mercy. Jazzy and stylish, set in a dreamlike version of the ’40s, “Nero Wolfe” is a terrific period drama, and a perfect blend of character and crime.

Justified

It would take a surplus of scientific proof to get us tired of Timothy Olyphant and his Infinity Stone collection of hard-living’ cowboy toughs. Raylan Givens, protagonist of “Justified,” may be his finest iteration. It’s a hard call, but at six seasons, Olyphant is given more room to flesh out Elmore Leonard’s modern marshal than he had as Seth Bullock in “Deadwood.”

Givens introduces himself in “Fire in the Hole,” a premiere episode drawn from a Leonard novella of the same name. It sets the tone for a stellar adaptation of Leonard’s economical but intricate storytelling. Raylan is a good but not perfect man born in the wrong time, a man who understands the boring but effective methods of winning a gunfight with a bad guy. His interpersonal relations are the heart of an otherwise anthological collection of story arcs and one-offs, marking time by the slow ways Raylan changes. Fans of “Yellowstone” or even new viewers intrigued by his time as Cobb Vanth on “The Mandalorian” owe it to themselves to see Olyphant in one of the finest hats a man can wear.

True Detective

To shove bias out of the way real quick, when I talk up HBO’s premier thriller series “True Detective,” I mean seasons one and three. Rust Cohle and Martin Hart, played by Matthew McConaughey and Woody Harrelson, respectively, tear up the first season with a decades-long mystery about a bizarre series of murders. It’s a platform for the dark philosophy that hides inside crime, delving into the fringes of horror. Though viewers (like me) uplifted the Lovecraftian elements into oversized prominence, it’s fairer to say season one is an exploration of the nihilistic philosophy of horror that Eugene Thacker explains in “In the Dust of This Planet.”

Season three returns to that mortal terror, a generational case about missing children and our own unreliable memories. The ever-stunning Mahershala Ali is balanced by his sleazy but loyal partner Stephen Dorff, in a surprising career resurrection. The only ghosts here are the haunts of a man fighting his dementia. It’s enough. The real mystery hunted in “True Detective” is how any of us can bear to be human.

Hannibal

Take an anthological crime drama, add Thomas Harris’ beloved villain Hannibal Lecter, and add the most sumptuous aesthetics to exist on television. Then cast Mads Mikkelson and Hugh Dancy, and make their vampiric dance of monstrous desire part of the constant background music of the weirdest crime scenes to make it onto broadcast television. “Hannibal” is, well, an entire feast for our senses, even the most taboo ones. It’s also an artful method of exploring the psychology of crime while putting the biggest monster of all dead in the center of it.

“Hannibal” is a love story about covetousness. Whether you ascribe to the all-but-blatantly canon romance between Lecter and Will Graham or not, the chemistry between them is intense enough to border on the sacrilegious. Lecter covets Graham, just as a variant of him once taught Clarice Starling in “Silence of the Lambs.” It’s enough to make the predator risk himself. Absolutely stunning stuff, but not for fans of gentler explorations of what brings out our most inhuman selves.

The Wire

If I have to sell an established crime fan on “The Wire,” I honestly don’t know what we’re doing here. If you haven’t seen it yet, you’re in for something truly special. The apex evolution of the world David Simon showed us in “Homicide: Life on the Streets,” HBO’s “The Wire” plumbs some of those same stories to tell all new ones about the broken souls corroding the entire city of Baltimore. From bottom to top, a web of corruption ensnares everything from streetwise drug lords to the Port Authority, to the city’s crumbling schools and infrastructures, and even refusing to spare the media bodies Simon himself worked for.

A wealth of fine actors inhabit the most complicated and sometimes hard to like characters in the medium. Idris Elba remains a stand-out as the Barksdale family advisor Stringer Bell. Lance Reddick is the lieutenant that catches the Barksdale special detail, our guide to the frustrating politics inside Cop HQ. Dominic West is Detective Jimmy “The f*** did I do?!” McNulty. Across five seasons, “The Wire” explores a realistic world. The series demands binging; you need to know what happens next. But take it from me. You’ll probably need a long break before moving on to the next season.