If it was always clear to readers that all disasters in the story were meant to happen and were somehow ultimately good, while major travesties weren’t possible due to a divine plan, some of the wind would be taken out of the sails of the story. In many ways, the nature of fate and free will is made excruciatingly clear by The Lord of the Rings to those paying attention. But these topics are philosophically challenging, so their debate in the LotR fandom is understandable. Plus, a little ambiguity on destiny in Lord of the Rings‘ Middle-earth is part of what makes the novel nail-biting.

The Lord Of The Rings Has A God Called Eru Ilúvatar & Eru Has A Plan

Fate Exists In The Lord Of The Rings

Fate and free will in Middle-earth are hotly contested by The Lord of the Rings fandom, and that discussion all swings around the One Eru Ilúvatar. Eru is the God of Middle-earth, modeled after the Catholic God of LotR creator J.R.R. Tolkien. Tolkien confirmed that LotR was not a Christian allegory, and he critiqued his friend, C.S. Lewis, for creating such a blatant Christian allegory in The Chronicles of Narnia. But he confirmed that there were allegorical elements to LotR. Eru is referenced in The Lord of the Rings, most explicitly in the appendices, where he is called “the One.”

The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, and The Road Goes Ever On were the only LotR works Tolkien published in his lifetime. Tolkien entrusted The Silmarillion – his standalone book summarizing the myths of LotR – to his son to finish editing and publish posthumously. Tolkien’s son did this but agonized over what to include, resulting in him following up The Silmarillion with the 12-volume The History of Middle-earth book series, compiled of works that were excluded from The Silmarillion. This series clarified The Silmarillion’s inconsistencies and dived deep into LotR lore.

Resultantly, Eru isn’t mentioned in Peter Jackson’s Hobbit and Lord of the Rings trilogies. But The Silmarillion revealed Eru in all his glory, clarifying what was suggested in Lord of the Rings. Eru enacts divine providence in Middle-earth, as confirmed by Gandalf, Tom Bombadil, and Elrond in LotR, discussing how chance meetings and coincidences are actually “something else at work.“ Fate is the manifestation of divine providence in the world, whereas chance is how divine providence appears to those who don’t understand the plan. Tolkien scholar Kathleen Dubs first vocalized this idea.

Eru Gave His Subjects Free Will In Lord Of The Rings, Making Them Accountable

Free Will Exists In The Lord Of The Rings

Despite fate, everyone in Middle-earth has free will. In his letters, Tolkien confirmed Eru as “never absent and never named,” controlling Middle-earth’s events to such an extent as to be “The Other Power” that “then took over” at the Cracks of Doom, ensuring Gollum’s fall into lava. And yet, Tolkien also confirmed in a letter that Elves and Men “were rational creatures of free will in regard to God.“ It certainly seems this way, from Lord of the Rings. Gandalf, possibly the closest thing the novel offers to a divine agent on Middle-earth, wasn’t blessed with total certainty and confidence.

In The Silmarillion, Eru criticized Morgoth for counteracting his will, suggesting Morgoth’s fault in the matter. Close reading of the legendarium demands the conclusion of both fate and free will operating in Middle-earth. Being modeled after Tolkien’s Catholic God, Eru is benevolent. If Eru is both benevolent and the executor of divine providence and fate in Middle-earth, the age-old question of the origin of evil arises here just as surely as it arises in the real world. But if free will is operative, then any of Eru’s lifeforms could choose to instigate evil in Middle-earth and are all accountable for their actions.

Although It’s Mind-Bending, Free Will & Fate Are Compatible In Lord Of The Rings

Characters Subject To Eru’s Plan Also Have Free Will In The Lord Of The Rings

It seems strange for free will to be possible in a world subject to God’s plan, but fate and God’s plan coexist in Middle-earth. Lord of the Rings powerfully suggests that Middle-earth is not deterministic, and indeed, it isn’t, which is key to its danger and loveliness. Tolkien scholars as diverse as Kathleen Dubs, Corey Olsen, and Tom Shippey agree that the Roman philosopher Boethius heavily influenced Tolkien, and Boethius explained how fate and free will coexist. Eru lives outside time, as Boethius asserted God did. So, nothing is preordained. There is only a constant unity of every single will.

Middle-earth is a continent in Arda, which is a world in Eä, the universe, which is located outside the Void and the Timeless Halls.

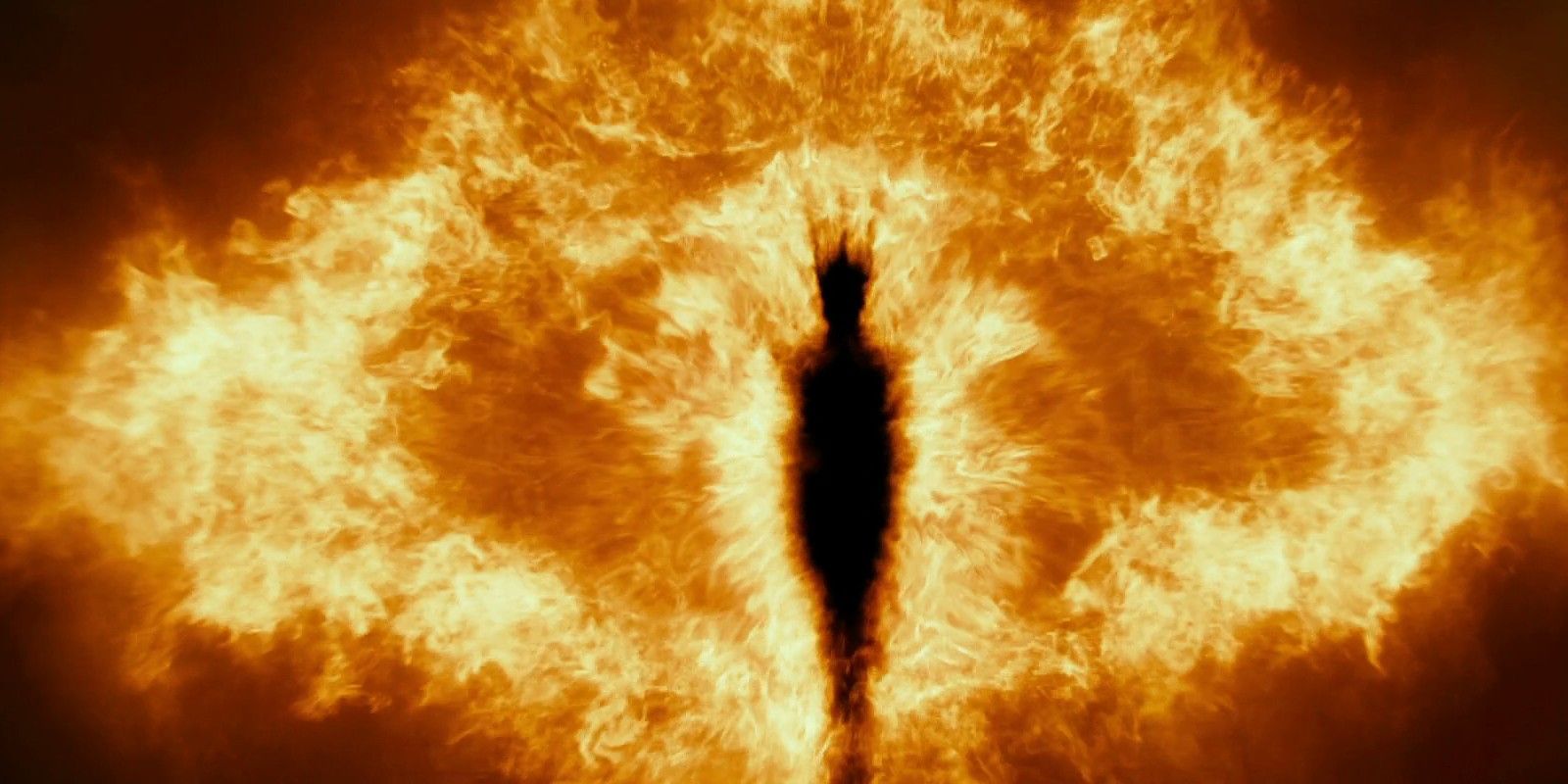

That may just be a radical and idealistic thing of great beauty. Boethius espoused these views in The Consolation of Philosophy, which he wrote in prison after being accused of treason, magic, and sacrilege, and before being torturously executed. Perhaps the truly new can only be forged in fire; Sauron could testify. Middle-earth was the world that Tolkien wished for, and in staunchly distancing it from allegory, he ensured that his use of Boethius’ vision was liberated from the complexities of real-world religion. Although inspired by a Christian writer, Middle-earth’s fate carries a powerful message for everyone – try hard and have hope.

Eru Is Benevolent But Subcreation Can Introduce Evil In Lord Of The Rings

Eru Didn’t Introduce Evil To The Lord Of The Rings

Examining fate and free will in Middle-earth confirms that both exist, allowing for the introduction of evil external to a benevolent God, but Tolkien addressed the origin of evil in Middle-earth in terms of creation and subcreation. As the One creator, Eru alone had the ability to bestow life, the Flame Imperishable. True creation was akin to godhood as no act was as divine as creation. Creation by any other being was subcreation. As such, creative acts, increasingly, as they were further removed from Eru, were vulnerable to pride and arrogance.

Middle-earth’s fate carries a powerful message for everyone – try hard and have hope.

The Valar subcreated nature in Arda, but Saruman subcreated his engines of war from nature, making them more vulnerable to corruption. Before Arda began, the Vala Morgoth, Middle-earth’s original villain, left his place in the Timeless Halls with Eru and the other Ainur to seek the Imperishable Flame in the Void. Morgoth’s desire to create life foreshadowed his desire to become God. In a letter, Tolkien described Morgoth as “the Prime sub-creative Rebel.“ The Vala Aulë also rebelliously sought to make life, but apologized when discovered, avoiding the “ruinous path” that Sauron followed Morgoth down. Tolkien confirmed that “Eä… subcreatively introduced…evil.”

Before Arda began, Eru guided the Ainur in the Ainulindalë, a song that partially visualized Arda and its history. Men in Middle-earth had “a virtue to shape their life, amid the powers and chances of the world, beyond the Music of the Ainur, which is as fate to all things else,” confirming that Men had a degree of exemption from providence. But all of Eru’s species in The Lord of the Rings were subject to a level of providence. From Eru’s place outside time, he constantly worked toward a good greater than anyone locked into time’s linear confines could ever understand.